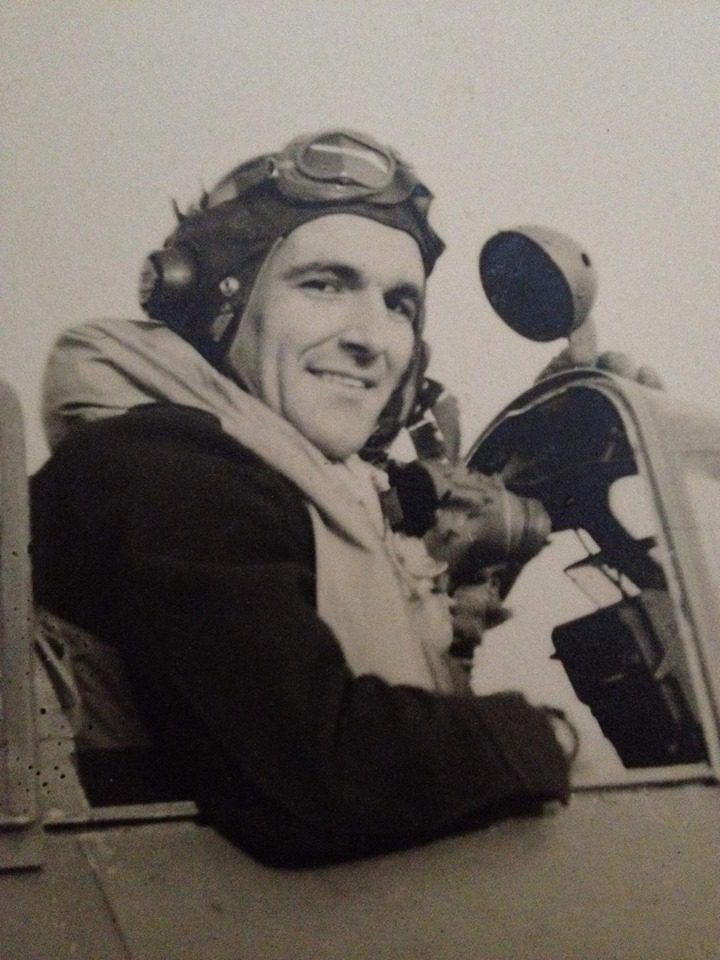

My father Cyril Devaux was born in 1920 into, at the time, British colonial St. Lucia. At 19, incredibly, he could be considered “senior” among frontline soldiers when the war in Europe began in September 1939. As Britain struggled under early Nazi gains, the colonies rushed to “do their part” and young men signed up in droves, no doubt spurred on by adventure, employment opportunities and a chance perhaps to do something completely different.

I understand my grandmother played chief spoiler in her son’s plans, managing to delay his departure to 1943 when he left for Alberta, Canada. By then, with the war’s tide firmly turned, dad’s formal training with the RCAF through the British Commonwealth Air Training Program (BCATP) stretched over 10 months from January to October 1944; light years away from the desperate few weeks crash course to get men flying in the opening stages, when Britain’s survival hung in the balance.

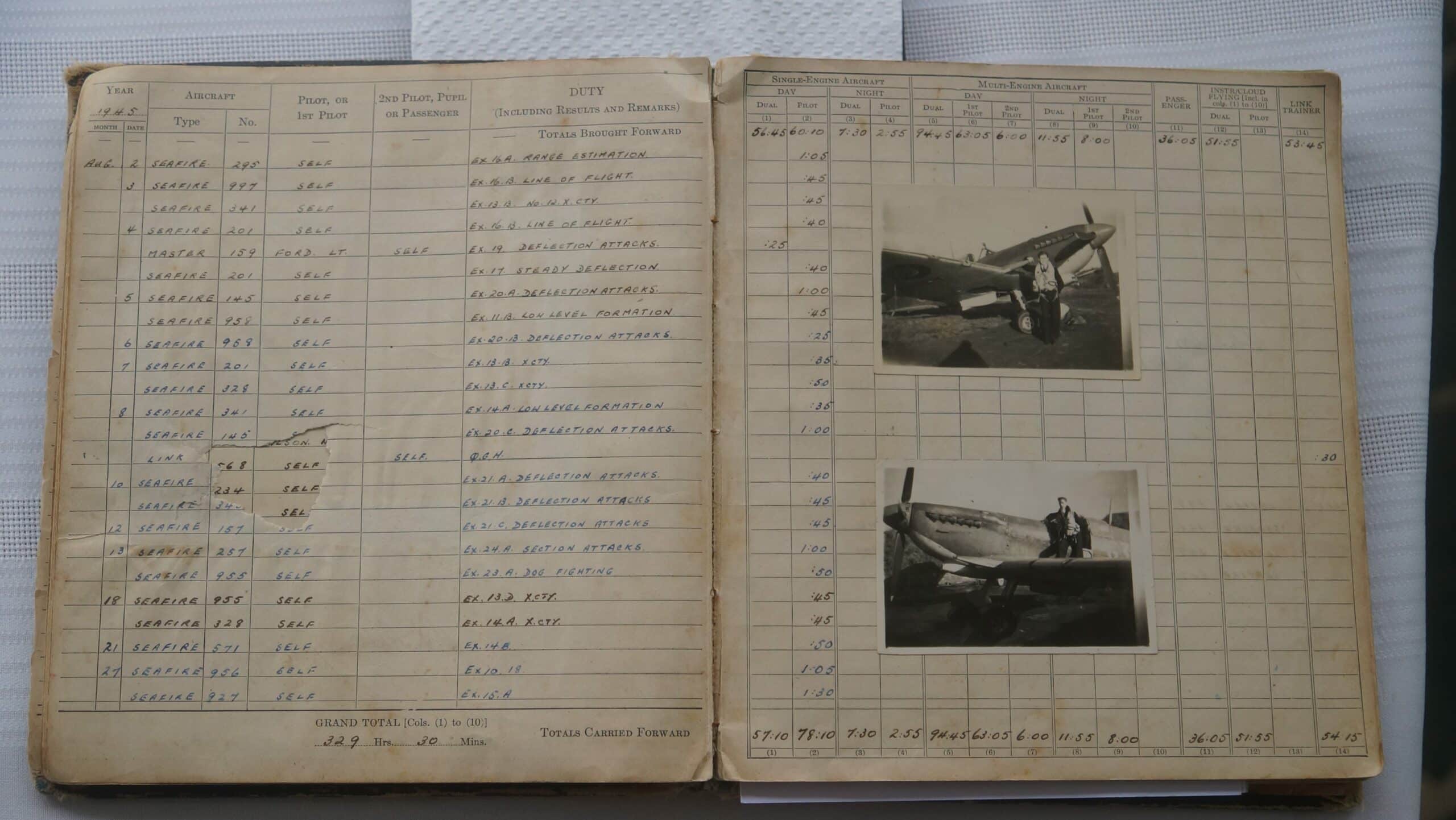

By the time he relocated to England early 1945, the Allied war machine was making steady progress towards Berlin and Tokyo so that my father never engaged in hostilities. With Berlin’s surrender in sight, he transferred to the Fleet Air Arm in order to serve in the Pacific. In July 1945, he was posted to Royal Naval Air Station (RNAS) Henstridge where he commenced training in Seafires (the iconic Spitfire modified for aircraft carrier service).

The atomic bombing and surrender of Japan in August 1945 meant that he was never deployed into combat however he continued to fly with the RNAS until May 1946, serving out his final months with 720 Squadron at Ford Sussex. After his discharge he returned to the West Indies where he rose to the level of Managing Director with Barclays Bank PLC, raising ten children with his wife Norah, before his retirement in 1980. He died on 6 February 1997; his tombstone reads “a noble man”.

Like the vast majority, dad never spoke of his military service and his war basically comprised a free aviation education. I now however, have a much better appreciation of the risks he faced evidenced by high trainee casualties, along with the perils of wartime Atlantic voyages and German V-1 rockets.

TLBP webmaster and aviation enthusiast, Lars McKie, has also patiently explained to me the challenges of progressing from slower aircraft to a high performance fighter (of the day) like the Seafire (marine version of the Spitfire) and in truth I realize I am lucky to be alive today. Still, neither my father nor I would ever compare his experiences to those who survived the true hell of combat.

When I was about 11, I stumbled upon his log book and instead of pouring over his impeccable handwriting, detailing each flight, I was immediately drawn to the few black and white photographs of the aircraft stuck in the book. I have never been especially enamored of planes but there was something absolutely magical about the gracefully engineered lines of the Seafire. The 11 year old that I was, proceeded to pluck the photos from the old book, damaging some of the pages in the process; 40 years later I am still searching for them. Thankfully I was smart enough to hold onto the book.

Nick Devaux, 2020