Castillo served on the mighty USS New Jersey (BB62), the ship that Admiral Halsey had selected and drawn with care as his Flagship. Although being more familiar with, and at home on, a carrier he could not risk having flag functions interrupted by battle damage to the vulnerable carriers. The only alternative as he saw it was that new Iowa class battleship that could keep up with the new 32-knot carriers.

Having had observers out on other ships to determine any deficiencies the flag plot of New Jersey was then extensively altered. Admiral Halsey’s Flag Allowance and staff consisted of 137 men in total at the time of boarding the ship. When coming aboard in August 1944, the ship has had changes made to make it the best in the fleet and was used as a model for the flag plot building the USS Missouri (BB63).[49]

It is at this time the journal entries of Castillo start to come in chronological order. The entire journal is written on single pieces of Memorandum sheets marked with “COMMANDER THIRD FLEET” at the top. It is a sobering thought when one digest and contemplate where, and under what circumstances, these pages are written.

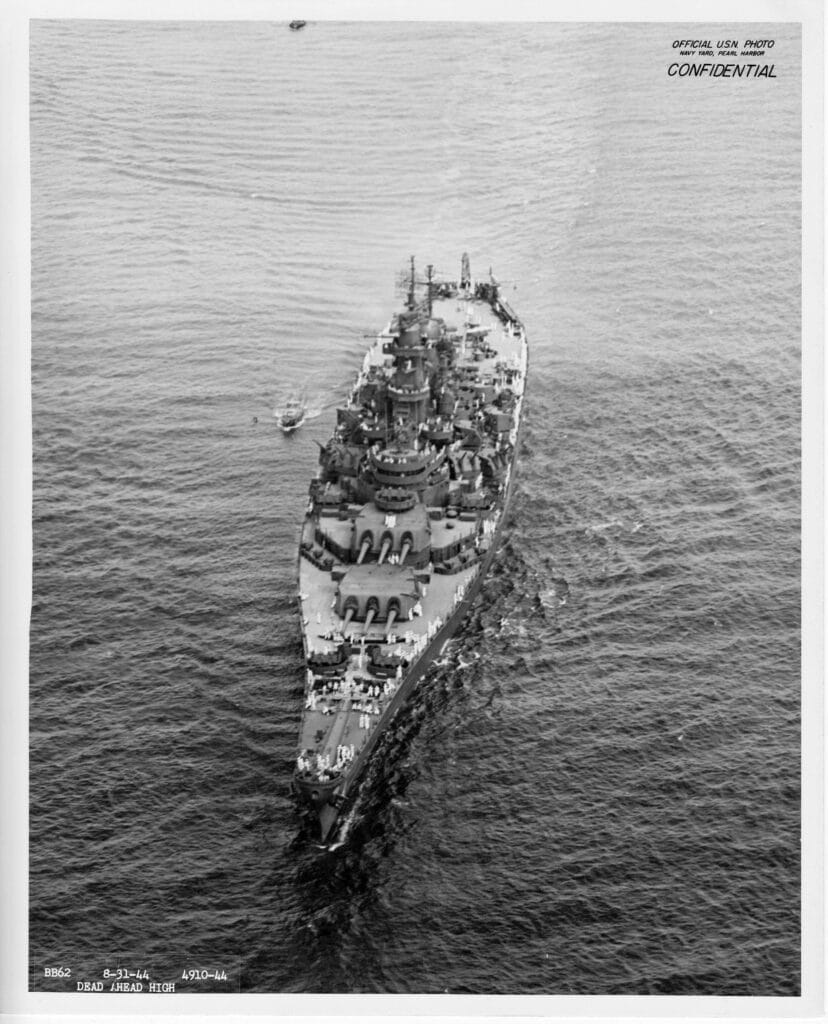

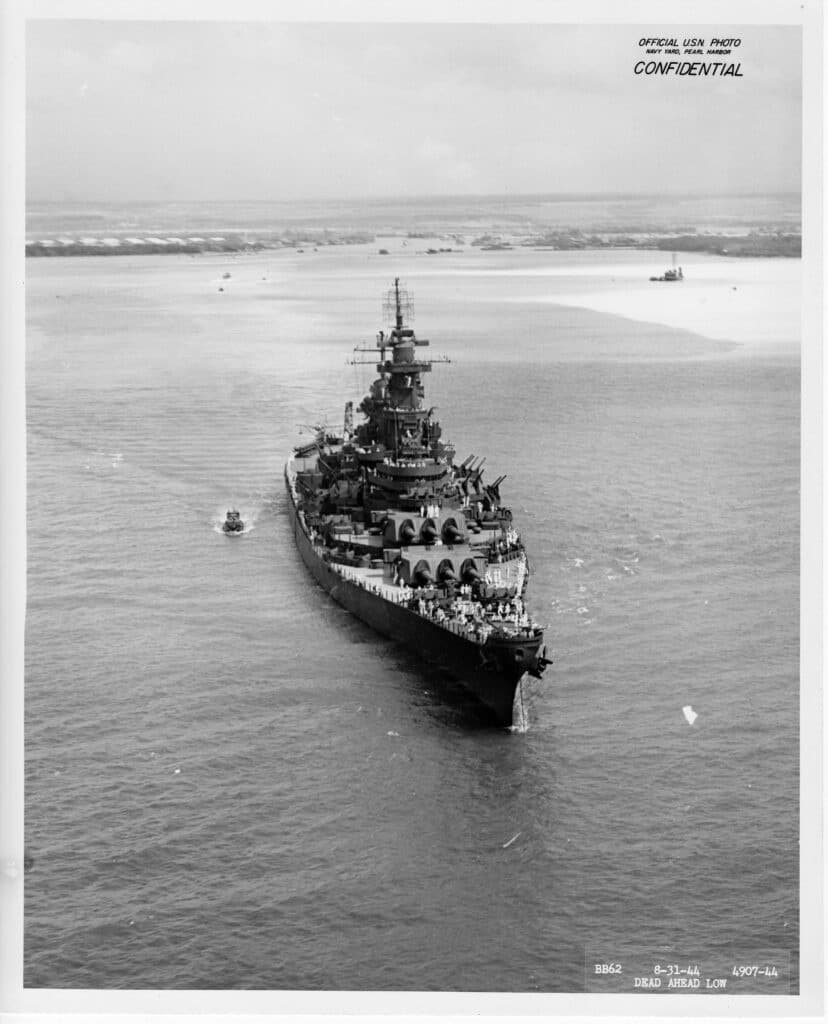

The below image of USS New Jersey (BB62) is stated to be taken at the time of her departure from Pearl Harbor. It is dated 31 August 1944 which cannot refer to the date taken as the ship was well underway on this date having departed 24 August per her war diary.

Conrad F. Castillo is somewhere onboard the ship at the time of these picture is taken.

USS New Jersey (BB62) – South Pacific, September/October 1944

Throughout September and October 1944, the New Jersey acts as Flagship for Third Fleet in various Task Group constellations launching air strikes from carrier. Attacking targets in the central Philippines they also support the amphibious landings on Peleliu and Angaur in the western Carolines.

Admiral Halsey intended to keep pressing the Japanese probing them for weakness until meeting resistance he could not overcome. With the initial successful attacks on central Philippines 12-13 September, he was now taking aim at what he considered to be a weak spot. The area being targeted was one with the largest concentration of enemy planes in Philippines – Manila.

Standing north eastward of Manila the night before the attack Admiral Halsey describes in his book an exchange with his Filipino stewards who Castillo was one of and could possibly have present during the Halsey’s adress.

The night before we struck, I called in our Filipino stewards and pointed out our targets on a chart of the city. I told them, “I want you to know what we’re going to do, because many of you have relatives in Manila. All of us pray that none of them are injured.”

Admiral Halsey, Admiral Halsey’s Story, chapter 11, page 202.[1]Admiral Halsey’s Story, Fleet Admiral William F. Halsey, USN and Lieutenant Commander J. Bryan III, USNR

Benedicto Tulao, a chief steward who had been with me for years, asked me, “Those are Japanese installations there, sir?”

“Yes.”

He said firmly, “Bomb them!”

The attack on military installations in and around the Manila area on 21 September 1944, were the first in the two years that had passed since having been driven from the islands. It must have been a surreal feeling for Castillo and his fellow Filipino comrades being back participating in, although fighting Japanese occupation, attacks on what was before their homeland.

Over the next several weeks the THIRD FLEET conducts operations launching strikes on targets on the Philippines. The journal entries tell of places being bombed; Cebu, Leyte, Negros, Panay and Manila Bay, an area that would be very familiar to Castillo.

By end September the fleet arrives Ulithi atoll after a brief stop at Saipan.

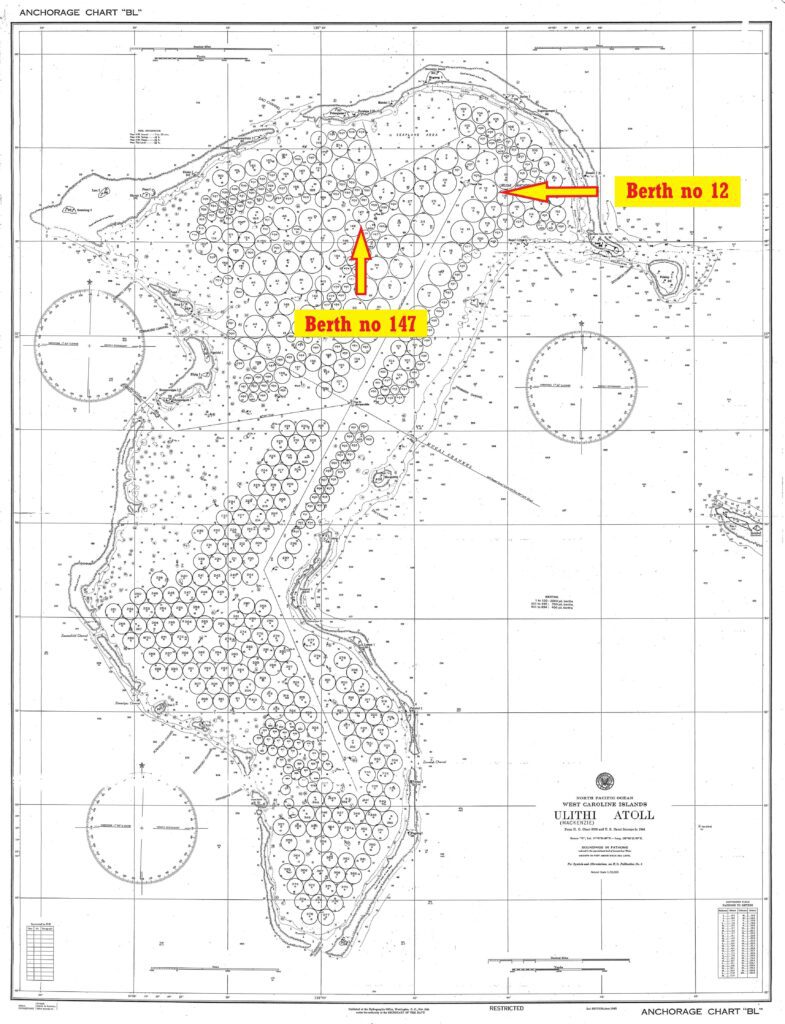

USS New Jersey (BB62) – Ulithi atoll and USS Essex October 1944

Ulithi is an atoll in the Caroline Islands of the western Pacific Ocean that the Japanese occasionally had used as an anchorage. The atoll with its large lagoon was ideally positioned to act as a staging area for the US navy’s western Pacific operations. On 23 September 1944 US forces landed on the atoll unopposed and within a month a complete floating base was in operation. Until the Pacific fleet moved its forward staging area to Leyte the Ulithi atoll was, for seven months in late 1944 and early 1945, the largest and most active anchorage in the world.

USS New Jersey dropped anchor 0658 on 1 October 1944 at berth No. 12 in the Ulithi Atoll and commenced provisioning stores from USS Aldebaran alongside.[2]USS New Jersey BB-62, War Diary October 1944, page 1 The atoll may be under US navy control but is by no means fully safe. The same days as Castillo and New Jersey arrives the minesweeper USS YMS-385 is sunk by a mine while clearing Zowariau Channel close by.[3]http://wikimapia.org/25589882/Wreck-of-USS-YMS-385

While the New Jersey is riding anchor in deteriorating weather on 2 October 1944 Task Group 38.3 stood in and anchored at 1715. One of the ships is USS Essex CV-9 where Castillo’s brother Freddie is stationed.

The Essex is anchored at berth No 147 and the New Jersey at No 12, the distance between the two brothers is less than 4 km’s apart in the Ulithi lagoon. The below Ulithi Atoll berthing map, with berths no 12 and 147 highlighted, coupled with the image of New Jersey from 6 November 1944, truly gives evidence of how massive the Ulithi lagoon is.

On 6 October the New Jersey get underway leaving Ulithi anchorage to continue operations.

Refuelling of ships and USS Mississinewa (AO-59)

Throughout his journal Castillo makes numerous mentions of refuelling ships. This refers to a support technique, developed and perfected in 1939-1940 by (then) rear Admiral Nimitz, where ships are refuelled while underway at sea. The technique became extensively used in the war permitting task forces to remain at sea indefinitely.[4]https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/c/chester-nimitz-development-fueling-sea.html

The procedure had the receiving ship come alongside the supplying ship travelling between 12-16 knots closing the distance to about 30 yards. After a messenger line is received the transfer rig and other equipment is pulled across. Although to some extent perfected, the process of underway refuelling was still a perilous endeavour.

An example of such difficulties occurred on 8 October 1944 as the New Jersey were to be refuelled where weather and seas played a role.

“1705 commenced making approach to go along starboard side of the USS MISSISSENEWA (AO-59) for fueling, and at 1736 tow line was secured. Delay in securing tow line caused by heavy cross swells, and the decrease in light. At 1911, after having unsuccessfully attempted to pass fuel hoses in heavy sea and swell, this vessel was directed to discontinue operation and resume station in task group formation.”

USS New Jersey (BB62) War Diary, 8 October 1944

In the war-diary of USS Mississinewa (AO59) the same event is described. After rendezvous with Task Force 38 at 0600 in the morning she immediately started to service the fleet. Through the day she serves carriers USS Hancock (CV19), USS Cabot (CVL28) and 5 destroyers. Notably, one of the destroyers served is the USS The Sullivans (DD537), in 1986 was declared a National Historic Landmark, currently still in existence as a museum ship on display in New York.

There is no specific mention in the war-diary of the failed attempt to refuel New Jersey, but the entry gives evidence of the difficult circumstances that day.

“This day the seas were very rough with fresh westerly gales. Fuelling exercises were very difficult. Hoses and lines were parted and much gear was damaged and lost overboard. This was the crew’s first heavy weather fueling at sea and every one behaved splendidly. Luckily there were no casualties except for a few minor bruises. On the well decks, the men were handling gear in seas that buried them and it was with great satisfaction that I saw them hand on like old timers.”

USS Mississinewa AO59 War Diary, 8 October 1944

The incident is however outlined in greater detail by Michael Mair in his book “Oil, Fire and Fate” whose father, John Mair, served on Mississinewa. Fuelling at sea under way in the best of seas was a dangerous endeavour. Already having light carrier USS Cabot (CVL-28) on her port side USS New Jersey (BB-62) initiated her approach on the starboard side. It was seemingly suicidal with two capital ships flanking the Mississinewa in foul weather and approaching darkness.

Imagining the three ships alongside each other’s under way, at such close distance, in seas that drenched the Mississinewa in the middle to a point it was greatly endangering the safety of the crew on deck, must have been a picture as profound and it would have been flat out scary.

Michael Mair explains in his book, that is in large based on interviews with surviving crew, that there were “choice words” directed at Admiral Halsey by the Mississinewa Captain Beck before reaching the end of his rope ordering the fuelling to be halted[5]“Oil, Fire and Fate” by Michael Mair, chapter “All Hands, Man Your Fueling Stations!”. With this detailed insight one can perhaps read more into how the entry in the war diary of New Jersey is ended; “this vessel was directed to discontinue operation” indicating it was not a decision taken by Admiral Halsey or Captain Holden, the New Jersey Captain.

3 days later the USS Mississinewa (AO59) rendezvous with Task Force 38 again and, among others, refuels the carrier USS Independence (CVL-22). The following images are taken from this occasion on 11 October 1944 and, even though there is no mention of foul weather or seas, they give a good insight of the conditions described.

80-G-290031

80-G-290030

USS Mississinewa (AO-59)’s steams alongside USS Independence (CVL-22) on 11 October 1944 during a replenishment at sea. Independence received the equivalent of 4,857 barrels of fuel from Mississinewa that day. On this day Mississinewa refueled nine ships over the course of 12 hours, transferring the equivalent of 40,264 barrels of fuel oil to one battleship, two carriers, two cruisers, and four destroyers.

The turbulence from the nearness of the ships causes them to roll and pull towards each other and amplifies the waves pushing one up to Mississinewa’s bridge level, towering over a sailor standing on the main deck.

The oiler USS Mississinewa (AO-59) will later be torpedoed and sunk on 20 November 1944 while anchored at Ulithi Atoll. Having replenished her cargo tanks to nearly full capacity she is anchored at berth No. 131 when hit by a Japanese manned “Kaiten” torpedo.

The ship sinks with the loss of 63 hands as well as the Kaiten pilot, she was the first ship to be hit and sunk by such weapon.

USS New Jersey (BB62) – October 12-14, 1944

For the most part up to early October 1944 the Third Fleet had not seen a major challenge by Japanese forces. This changed as strikes were initiated directly at Formosa (today Taiwan). Having attacked the Ryukyu Islands days earlier the Task Group now launches the first of several waves at 05:00AM on 12 October.

Over the next few days, the Japanese will respond which Castillo will note in subsequent journal entries.

Oct. 12, 1944 Thursday night at 7:00PM. A group of jap plane are coming. Now they are above us, they are dropping flare, more flare, outside is as bright as day time. Our ships is raided with bullets, one of our signal man are hurt by jap shrapnel. We shot down 6 jap plane and the thing lasted till 3:15 AM.

Conrad F. Castillo journal – page 9

In the war diary of USS New Jersey (BB62) the tale of this aerial battle spanning several hours emerges. The Task Group manoeuvres to keep approaching raids astern or on the quarter. From 1840 through the night to about 0200 the next day attacks are sporadic but constant. In total about 90 Japanese aircraft were sent to attack the carriers, 54 aircraft failed to return.[6]Philippines Campaign, Phase 1, the Leyte Campaign 22 Oct 1944 – 21 Dec 1944 by C. Peter Chen The dropping of “excellent flares in almost perfect position” was a concern but the Japanese were, evidently, unable to capitalise on them. No concerted torpedo, bombing or strafing attacks were pressed home. At least five enemy planes were observed crashing in flames near the formation, in two cases barely missing landing on a carrier deck.

The following day, 13 October, the Task Group continues to attack Formosa, Pescadores and adjacent islands.

Oct. 13, 1944 – Friday – 6:45PM H.Q. Here come the jap raider. Outside heavy firing is going. We shot down. One of our ship, cruiser Canberra was damaged.

Conrad F. Castillo journal – page 10

When giving a larger context to Castillo’s entry above it covers the event where USS Canberra (CA-70) is torpedoed with the immediate loss of 23 sailors killed in the explosion. With engine room flooded she is dead in the water and is taken in tow by USS Wichita.

The Task Group remain in the waters east of Formosa to offer some protection to the crippled USS Canberra under tow. They are within reach of Japanese land-based planes and raids were to be expected.

At 1518 on 14 October 1944 the New Jersey herself takes an enemy plane under fire with machine guns as it crosses astern from port to starboard. The plane is observed to go down in flames and the war diary notes ship ceased firing on 1519.

Over the course of several days the Task Group has poked the hornets’ nest further north than before. Reports provided to Japanese leaders from the battles were so inflated and false that Radio Tokyo reported 11 carriers, 2 battleships and 2 cruisers sunk. There was, Radio Tokyo added, great celebration in the streets and warm congratulations from Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini.

Furious but somewhat amused Admiral Halsey sent a despatch to Chester Nimitz who, on 19 October, was happy to inform the world that he had received from Admiral Halsey “the comforting assurance that he is now retiring toward the enemy following the salvage of all the Third Fleet ships recently reported sunk by radio Tokyo”. [7]Admiral Nimitz: The Commander of the Pacific Ocean Theater By Brayton Harris – p150

The next day, 20 October 1944, right on schedule the Leyte landings commenced. The Third Fleet supported by launching air strikes against targets on northern Visayan Islands. Castillo and his fellow Filipino comrades onboard would surely have felt some joy understanding that the beginning of the liberation of Philippines had started.

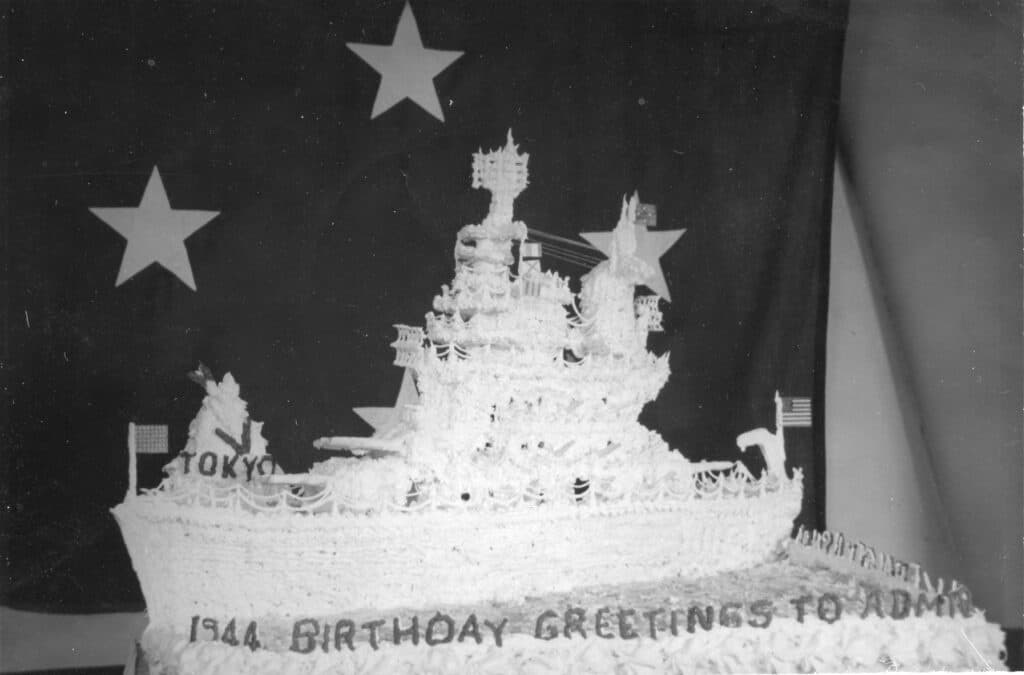

Birthday cake at sea – October 30, 1944

Admiral Halsey’s birthday was 30 October and in 1944 he celebrated it on board the New Jersey at sea east of the Philippines. In what must have been a welcome respite from normal operations Castillo notes making chicken salad for lunch and serving a beautiful cake made by the ship baker. Worthy to note is that said ship baker was Maximiano Tulao, brother of CStd Benedicto Tulao.

Steaming eastward a turkey dinner was served followed by desert in the form of a battleship cake with birthday greetings to the Admiral. During the dinner music was played by the USS New Jersey boys and later in the evening there was movie shown raising morale greatly.

The next day is spend refuelling all ships at sea and by November 1st the Task Group is heading back towards the Philippines to resume operations.

Picking up survivors

There are several entries in the journal by Castillo mentioning picking up Japanese survivors. In all cases this refers to survivors picked up by other ships and delivered to the USS New Jersey for “interrogation by ComThirdFleet personnel”.

The information below is obtained from the war diary’s of USS New Jersey (BB62).

22 October, 1944 – picked up from a downed “Betty” and received from USS Helm (received 16 October from USS Franklin)[8]USS NEW JERSEY – War Diary, 10/1-31/44

SHINCHIRO, Ono, (CPO – aviation)

AKEO, Sawara, (leading seaman)

KOGI, Ogawa (leading seaman)

TOYOKICHI, Miyotake (leading seaman)

26 October, 1944[9]USS NEW JERSEY – War Diary, 10/1-31/44

Two POWs received on board – no names stated in war diary.

27 October, 1944 – most likely survivors from cruiser sunk night before[10]USS NEW JERSEY – War Diary, 10/1-31/44

KOBOYASHI, Yonyiharu, S1c

NISHIMURA, Toshiyo, S1c

YAMADA, Taros, S1c

MASUDA, Hisakuchi, S1c

16 November, 1944 – received from USS Thorn[11]USS NEW JERSEY – War Diary, 11/1-30/44

YOSHIO, Nihei, Chief Aviation P.O. (naval), age 21

With the little information found it appears that it was common practise for survivors to be picked up by smaller ships in the screen and to, when convenient, deliver them to the Flagship for interrogation. At what point these POWs then left the New Jersey is unknown, but most likely transferred off to an oiler or supply ship for further processing.

The below image is taken by Lt. Cmdr Fenno Jacobs, a photographer from Naval Aviation Photographic Unit, while on board the New Jersey. The photograph has a caption describing Japanese POWs being deloused, bathed, and issued GI clothing as soon as coming on board the ship.

The image, one of several in a series, is claimed to be on the after-deck of the New Jersey in November 1944. The occasion has clearly been staged and drawn a large crowd of both officers and enlisted men which would indicate that ship is within relatively safe waters.

The photographs illuminate the stark contrast between the two sides. By October 1944, the Philippines had been largely cut off from resupply leaving the Japanese short on food and unable to control camp vermin.

It was standard procedure to throw overboard or burn their clothes and issue American uniforms to prevent spread. It was probably not a standard procedure to make, what appears to be, a humiliating public spectacle of the process. It is however not for us to pass any judgement 80 years later without the full story or circumstances.

A new strategy – October 1944

The American advance to retake the Philippines was imminent in October 1944 and the Japanese measures to prevent it became desperate. Exactly how ‘Kamikaze’ suicide missions were conceived and developed into an accepted strategy is a topic to large and complex to cover here.

The first organised Kamikaze missions of the Philippines were flown in October of 1944. Pilots of the ‘Shikishima Special Attack unit’ were, on their 5th sortie, the first to successfully sink a ship. Slamming into the escort carrier USS St Lo (CVE-63) on 25 October 1944 just east of Tacloban the carrier sinks in 30 minutes. While the St Lo sinks the New Jersey, with Castillo on board, is conducting operations further northeast of Luzon. Surely, they would have been made acutely aware of the Kamikaze tactics entering the scene of battle.

It is about this time there subtle, but distinguishable, transition in tone for Castillo’s journal entries. He moves from recounting Japanese aircraft ‘bombing’ the ships, to ‘diving’ on the ships and, as with the entry on 29 October.

Lunch time – a jap raider are attacking us. He is dropping bomb and diving on carrier. Tojo was shot down and he try to crash his plane on our carrier, he almost hit it, only ½ yard away from the carrier. We shot down two tojo plane.

Conrad F Castillo journal – page 17

There is no doubt in what profound impact and impression the Kamikaze attacks have had. Unbeknownst to Castillo at the time he will come to witness many more attacks of this kind.

For all parts in the series see below:

- Conrad F Castillo – Part 1 – Beginnings

- Conrad F Castillo – Part 2 – New Zeeland

- Conrad F Castillo – Part 3 – Noumea

- Conrad F Castillo – Part 4 – USS New Jersey BB62

- Conrad F Castillo – Part 5 – Mog Mog, Kamikazes and Typhoons

References

Be the first to comment