Our human experience includes a myriad attractions and aversions developed over a lifetime. I don’t recall how I became aware of WWII, but it immediately interested me as a child. The sheer scale of terrain, resources and lives consumed, the technological advancements, the divisions and alliances, the events leading to, and those since shaped by it, all seemed worthy of deeper understanding. Ours is an increasingly complex interdependent globe where information abounds, overloads and overwhelms. We struggle to process the current, far less the historical. The political climate of the last 4 years, accentuated now with Covid-19, coincidentally frames The Log Book Project’s (TLBP) own timeline. Concepts of fact, truth, accountability, transparency and perhaps most importantly, trust, have come under intense scrutiny. There is an additional burden of proof today that was unnecessary 4 years ago. For better or worse, the way societies filter and process information is evolving, directly affecting decisions, opinions and ideologies. Where this leads appears to be anyone’s guess at the moment but it has reaffirmed for me the importance of appreciating the lessons of WWII while celebrating those who opposed tyranny and sacrificed everything for our freedom.

The beginning

In early 2016, I read a BBC article about a Japanese fighter pilot named Kename Harada who reportedly downed 19 Allied aircraft in service that included the Battle of Midway. Harada himself survived being shot down at Guadalcanal. In post war Japan, he struggled to reconcile the violence he had witnessed and been part of, and in later life he founded a nursery for children and subsequently a kindergarten. He became an outspoken peace advocate and remained a prominent speaker until late in life. Harada’s story prompted the sudden spontaneous idea of asking him to autograph my father’s logbook. There immediately presented the dual challenges of language barrier and a small matter of 8,700 odd miles; one way from St. Lucia where I live.

I managed to contact his family who replied that his health was poor but I could try later in the spring. It so happened that my then OECS boss, was required to visit Japan and, having secured the agreement of Richard Howard and his wife Yoko, associates in Japan, I decided to send the book off in advance. I figured the worst that could happen was that Harada would refuse to sign and I would just have the book sent back. I realized I was in denial about the “worst” when the day came to actually place the book in the envelope. Sweating profusely and with every alarm bell sounding in my head, I presented the book to my boss to transport to Japan. He was equally horrified when I explained the contents and mission and tried his best to dissuade me, almost refusing to take it.

Needless to say I was just a tad apprehensive for the next few days until Howard confirmed receipt of the book in Japan. Contacting persons well into their 90s is a delicate affair, especially when they are unwell. One is never quite sure when or how to follow up. A few weeks later Harada sadly passed away and thus I was never able to get his signature or his firsthand account.

Now what?

There are “now what?” moments when your favorite pizza joint is closed, or the movie you wanted to see is sold out, and then there are “now what?” moments when a prized irreplaceable family heirloom is on the other side of the planet faced with a real-life mission-impossible.

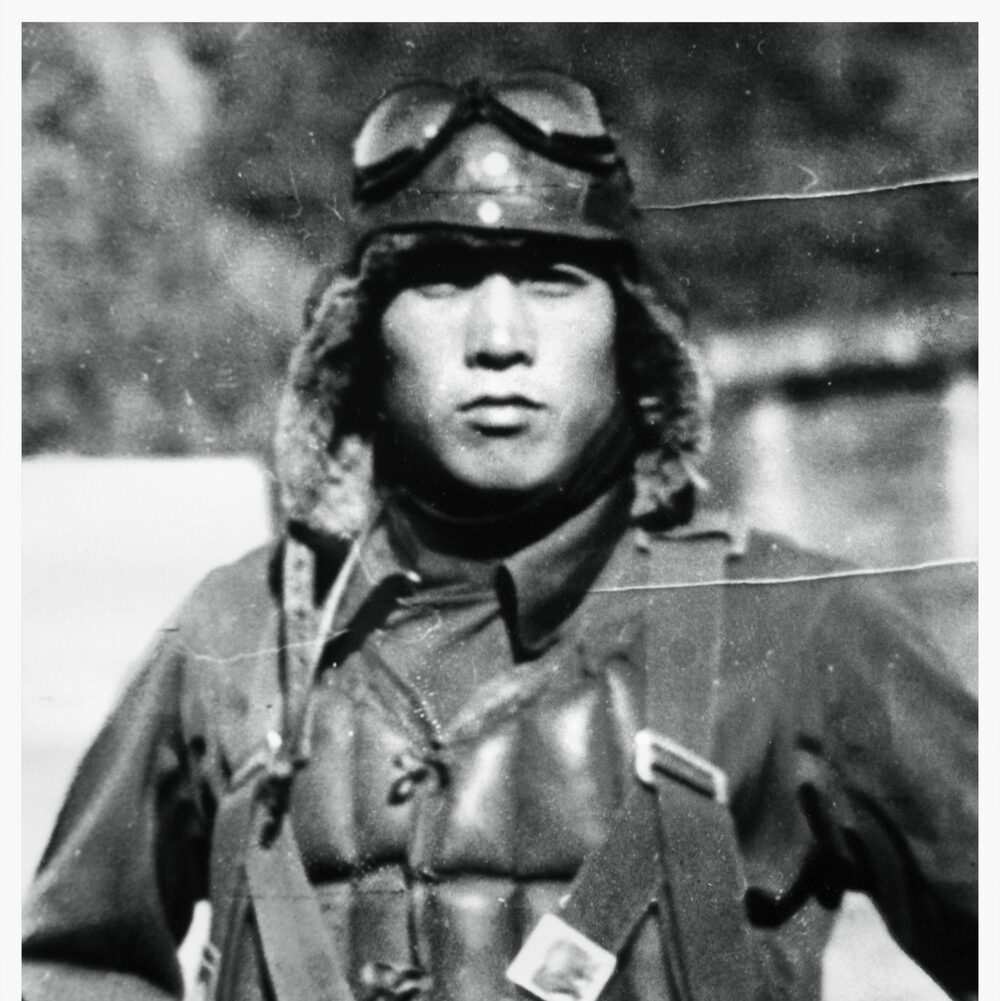

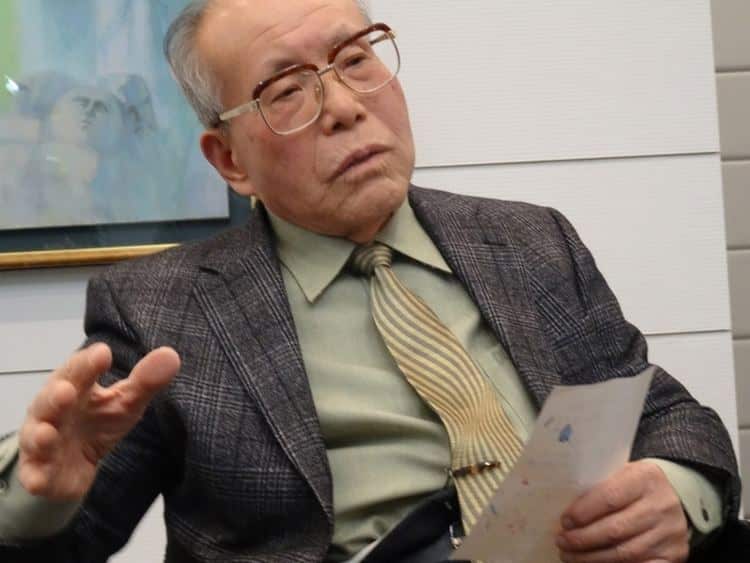

Within a few days I read of US President Obama’s May 2016 visit to the Hiroshima memorial where survivor Shigeaki Mori was officially present. Mori not only survived the atom bomb, but subsequently dedicated years of his life tracking down the families of US POWs who perished in Hiroshima. Mori felt strongly that these American men deserved recognition among the list of Japanese victims on the city’s memorial. His tenacity and dedication led to the names of the fallen US servicemen eventually being included.

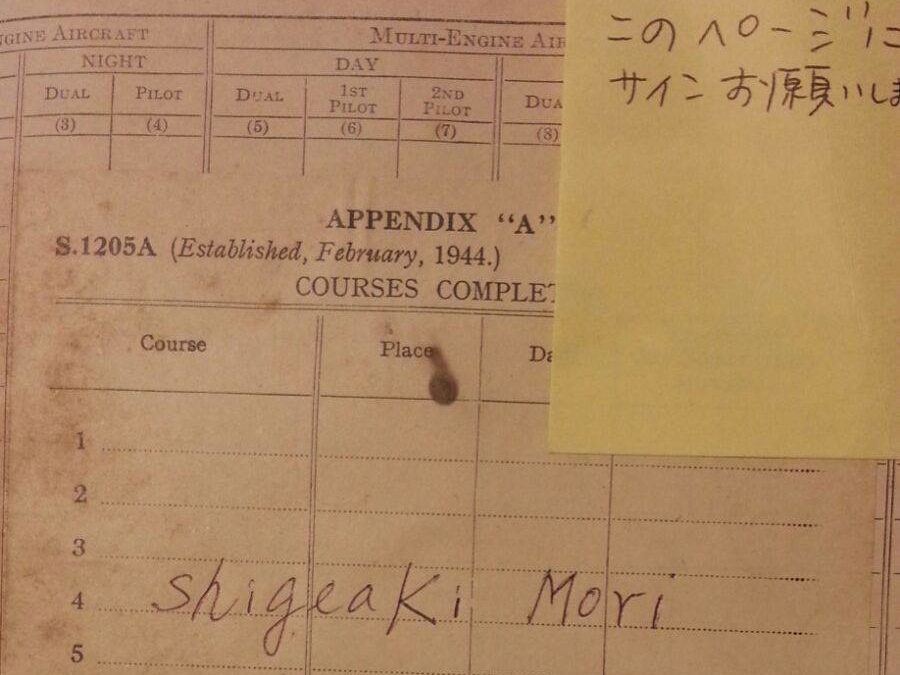

Mori’s compelling story, beautifully captured in director Barry Frechette’s documentary, Paper Lanterns, was the answer to “now what?”. Contact was established and thrillingly he agreed! Except that he would be unable to sign until his health improved during which time he would be hospitalized. Suddenly this sounded all too familiar. A few weeks later, in July 2016, Howard sent me a photo of Mori’s name humbly and simply written on the last page: thus began The Log Book Project.

The journey

4.5 years, 3 times round the world, and over 100 signatures later, I have never forgotten Kename Harada and the impetus his life story gave me to start this project. I would love to have a Harada family member autograph the book on his behalf. Perhaps that would be a fitting way to end the journey. For now, the business of obtaining the signatures remains a priority as several veterans have agreed to sign and sadly passed away before they could. The journey itself has very much taken on a life of its own, and the generosity of persons who have readily volunteered to assist is simply remarkable. A network of volunteers and contacts now exists that I could never have imagined at the outset. Among many stellar enablers, Ross Stewart, curator of the Wethersfield Airfield Museum in Essex, UK, has performed yeomen service along with the aforementioned McKie. Todd DePastino, Nikolai Mongroo, Margaret McEvoy and recently Mike Mair are among those to whom, along with my siblings, I am indebted. I am the richer for all the encounters.

And then there are the signatories’ stories. A document summarizing their remarkable experiences, annotated with the Log Book’s own journey, is in progress. It may take years to properly complete. As the journey unfolded, certain common themes and threads began to emerge. The impact of the Great Depression, the innocence and vitality of youth, dedication to duty, sexism/racism within the armed forces, the importance of family, the carnage of combat, the pain of loss, PTSD and the journey of reconciliation. The heightened US racial tensions of 2020 have amplified a subset within the logbook; African-American US servicemen and women who, during WWII, incredulously offered their very lives to defend rights and privileges denied them. The ignoble treatment of these stoic heroes has been an incredible learning experience, and underscores the general treatment of persons of color from around the Commonwealth who overcame racial barriers and other hurdles just to offer their services as valiantly as their white counterparts.

Viewpoints

A cursory read of WWII events reveals extensive horrific suffering and deprivation visited upon millions – on all sides. Inspired by Harada and Mori’s amazing examples, I immediately realized TLBP would be more compelling by having viewpoints of former German and Japanese veterans. I discovered two extremely compelling stories of former enemies meeting in friendship as senior citizens. The first involved former ball turret gunner Les Schrenk who spent 15 progressively brutal months as a POW after his plane was downed in February 1944. The German pilot who shot and disabled Schrenk’s plane crucially allowed it to fly to nearby Denmark instead of forcing the crew into the frigid North Atlantic. Schrenk, convinced his life had been spared, spent years searching for the mysterious pilot and eventually in April 2012 visited veteran Hans Hermann Müller at his daughter’s home in Germany. The visit is well documented and bought tremendous closure for Schrenk concerning an extremely traumatic period of his life. He recalled of the meeting “saying goodbye was very hard. Neither of us wanted to part. We had become very good friends and sadly said goodbye”.

The other concerned a meeting of former adversaries Victor Gregg and Günter Halm at a Chalke Valley History Festival in Salisbury in 2016. Both these men lost comrades in brutal fighting at the Battle of El Alamein during WWII.

Gregg said subsequently of the encounter

There is some sort of comradeship among men who served on the front line and who put their lives at risk every day, no matter what side they were on. I think that comradeship was there when Gunter and I met. We recognized it in each other. Naturally, he had been on one side trying to kill me and I was on the other trying to do the same. But there was no animosity whatsoever between us. We have both had a hard time of time of it.

Schrenk signed the logbook in 2017, sadly Müller was too ill and has since passed away. Gregg also signed and although Halm agreed to sign, he sadly passed away prior to the book’s arrival in Germany. His wife Regine Halm signed in his stead and kindly offered to obtain the signatures of other German veterans. Only later did I realize that some of these men were veterans of the much feared SS units.

Perspectives

How then to treat with their signatures in a document intended as a tribute? As of this moment I am not aware of any direct involvement of any of the signatories in war crimes. But it is entirely possible that this is the case given their membership in the SS. There is no attempt here to romanticize the tyranny of Nazi or Japanese war crimes and atrocities or indeed that of any other individual, group or nation involved in WWII. Then, as now, front line fighting was conducted mostly by young men, boys actually, who, stripped of their individuality, were forged into forces highly trained in the business of ending life. TLBP therefore also seeks to gain perspective by examining the experience of the individual within the machinery and madness of war. My interaction with veterans generally, indicates that professional soldiers will readily give their lives for the comrade alongside, long before considering the ideologies and causes of those directing far from the front line. If it is discovered that war crimes were committed by any of the Log Book signatories, it will be presented in all its heinous reality, and duly condemned, much as one would visit a holocaust museum to gain deeper understanding – absolutely not to glorify. It is important to understand that the perpetrators of these incomprehensible acts were real people who shared a generally common geographic/cultural/educational/social background with their victims. These crimes therefore are further reason to celebrate those Log Book signatories who opposed such evil.

We can also recognize that for some adversaries of WWII – men like Harada, Halm and Müller – there was a duty to defend their countries in accordance with the accepted guidelines of combat, often carried out valiantly and with great honor. Ultimately however, I hope the most important legacy of TLBP serves to promote peace while highlighting war’s futility. There is so much more that unites earth’s peoples than divides them if we choose to look beyond our biases and preconceived notions.

The future

The final question of what finally to do with the logbook remains.

On one hand it is priceless and unique and on the other, quite ordinary. Though I am immensely proud of my father’s service record, his logbook is one of thousands documenting similar experiences. The signatories’ stories however, have transformed this humble book into a powerful symbol of selfless service, reflection and reconciliation. The Log Book Project is therefore a tribute to all who suffered irreplaceable losses and all who served to purchase the freedoms so often taken for granted today. The book’s future value however, comes from continued research into the expanse of WWII and our retelling of the signatories’ stories. Otherwise the vital lessons they offer remain lost to history.

– Nick Devaux, December 2020