As a courageous Tuskegee Airman Alexander Jefferson served as a fighter pilot in the legendary “Red Tails” squadron. Defying both enemy fire and deeply entrenched racism Alexander Jefferson not only battled the Luftwaffe but also helped dismantle barriers in the segregated U.S. military.

Early Life and Military Entry

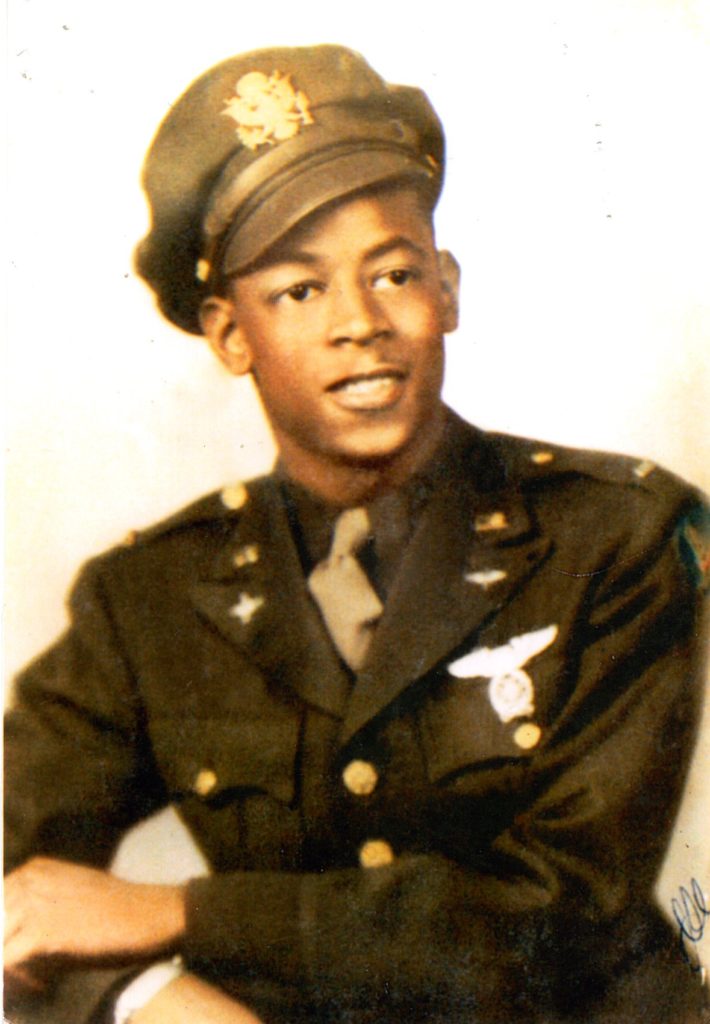

Alexander Jefferson was born on November 15, 1921, in Detroit, Michigan, into a middle-class African American family. He earned a degree in chemistry and biology from Clark College in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1942. Despite the deep racial segregation of the time, Jefferson was determined to serve his country.

He applied to join the U.S. Army Air Forces and was accepted into the Tuskegee Flight School in Alabama — the training ground for the all-Black pilot unit created during WWII due to pressure from civil rights activists and the Black press.

Tuskegee Airmen and Training

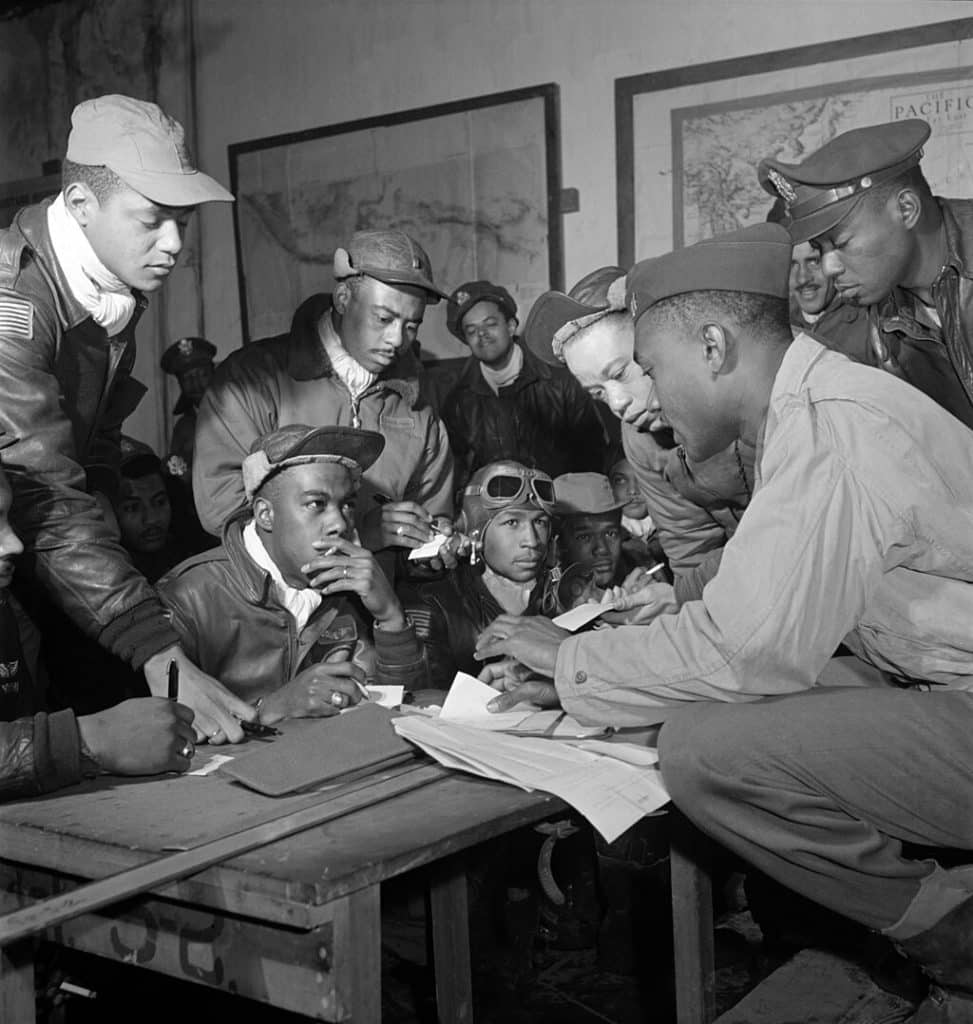

The Tuskegee Airmen were the first African American military pilots in the United States Armed Forces, serving during World War II at a time when the military—and much of American society—was still segregated. Trained at Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama, these aviators and their support crews formed units such as the 332nd Fighter Group and the 477th Bombardment Group, flying missions in Europe and North Africa.

Their combat performance was exceptional, particularly in bomber escort missions, where they earned a reputation for protecting American bombers with fewer losses than average. Flying aircraft like the P-51 Mustang, often with distinctive red-painted tails (earning them the nickname “Red Tails”), they shattered myths about Black inferiority in combat and aviation.

Beyond their military accomplishments, the Tuskegee Airmen were trailblazers in the struggle for civil rights. Their success directly challenged the U.S. military’s official policies of segregation and helped pave the way for President Harry S. Truman’s Executive Order 9981 in 1948, which desegregated the armed forces.

Their legacy is not only one of heroism in the skies but also of resilience, dignity, and resistance in the face of discrimination. The Tuskegee Airmen laid a foundation that inspired future generations and marked a pivotal moment in the ongoing fight for racial equality in America.

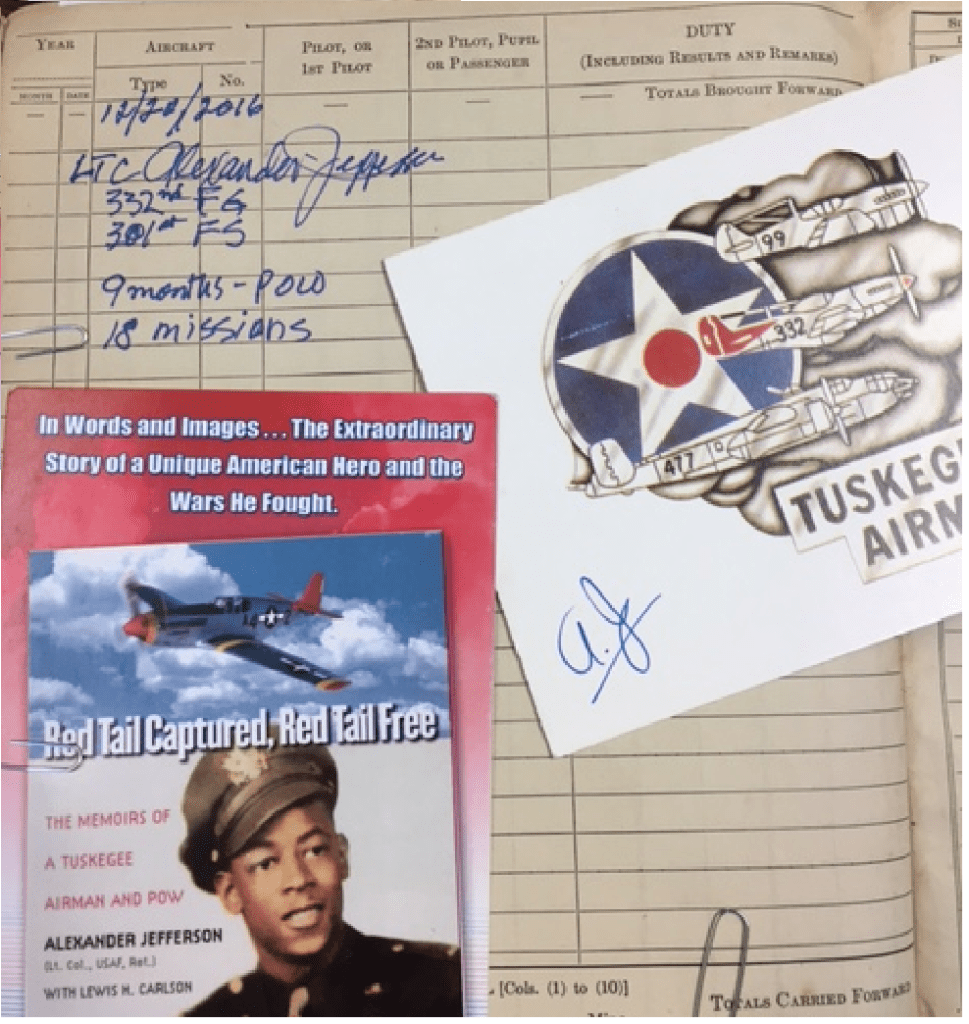

Jefferson trained as a fighter pilot at the Tuskegee Army Air Field, graduating in January 1944. He was assigned to the 332nd Fighter Group, specifically the 301st Fighter Squadron — one of four squadrons within the group.

Combat Missions in Europe

In the summer of 1944, Jefferson was deployed to Italy. From their base at Ramitelli Airfield the 332nd Fighter Group carried out long-range missions across Europe, primarily bomber escort duty — flying alongside Allied bombers to protect them from enemy German fighters.

The Red Tails developed a reputation for discipline and exceptional protection of the heavy bombers, such as B-17s and B-24s. Unlike some escort units that would leave the bombers to chase enemy aircraft, the Red Tails often stuck with their bombers, prioritizing mission success and safety over personal glory.

As a result, bomber crews specifically requested the Red Tails for protection on dangerous missions deep into enemy territory — a remarkable endorsement in an era when racism was still rampant in both military and civilian life.

The 332nd Fighter Group flew more than 15,000 sorties and completed over 1,500 missions during the war. They earned over 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses, and while their “no bomber lost” record was later revised, their low loss rate remained among the best of any escort group.

These missions were high-stakes and demanding, often lasting hours over enemy territory. Jefferson flew a total of 18 combat missions before his aircraft was shot down.

Shot Down and Captivity

On August 12, 1944, while flying a mission over southern France in preparation for the coming Operation Dragoon. Jefferson was attacking a radar installation near Toulon when his plane was hit by ground fire. He managed to eject safely but was captured by German forces almost immediately after landing.

He was sent to Stalag Luft III, a prisoner-of-war camp primarily for captured Allied airmen. This camp was infamous for the “Great Escape” that took place months earlier. Jefferson endured nine months as a POW and during his period of internment, Jefferson comments that he was treated like any other Air Force officer by his German captors.

As the war neared its end, Jefferson and other POWs were forced on a grueling march westward to avoid the advancing Soviet forces. This so-called “death march” was brutal, carried out in freezing temperatures with limited food and shelter. Many prisoners did not survive.

He was eventually liberated in April 1945 by Allied forces as Nazi Germany collapsed.

Return and Legacy

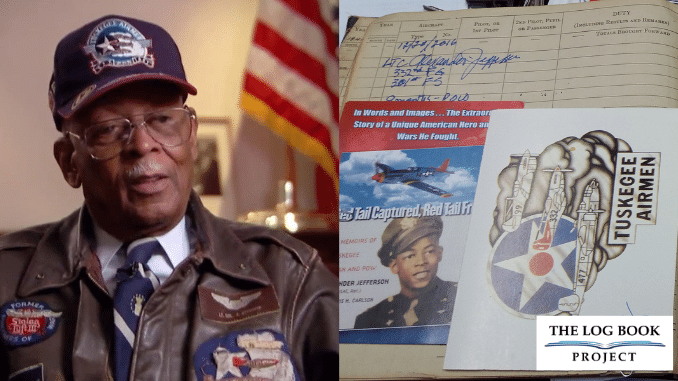

After returning to the U.S., Jefferson faced the bitter irony of coming home to segregation, despite his service. In his memoir, Red Tail Captured, Red Tail Free, he reflects on how he was treated better as a POW in Germany than as a Black man in his own country after the war.

Having been treated by the Nazi’s like every other Allied officer, I walked down the gang plank wearing an Army Air Corps Officer’s uniform towards a white US Army sergeant on the dock, who informed us “Whites to the right, niggers to the left.”

Alexander Jefferson

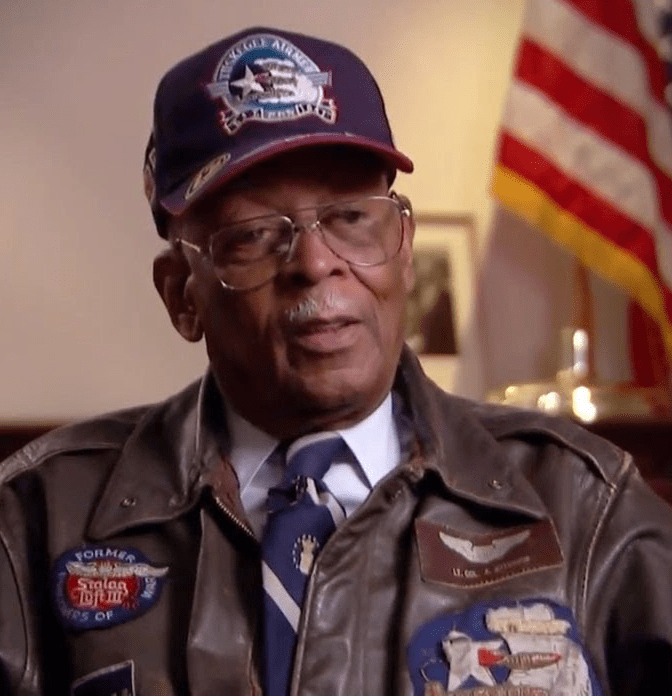

Still, Jefferson remained in the military as a reserve officer and later had a long and impactful career as an educator in Detroit. He was an active speaker about the Tuskegee Airmen and a champion of civil rights and veterans’ recognition.

In 2007, Jefferson and the other Tuskegee Airmen were collectively awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, one of the highest civilian honors in the United States.

Obtaining the signature

We first made contact with Jefferson’s granddaughter, Earnestine Lavergne. She very kindly agreed to facilitate my request for her grandfather to sign the Logbook.

It is striking how different Jefferson’s POW experience is compared to that of another log book signatory and WWII veteran, Lester Schrenk.

In his book Jefferson describes relatively humane treatment where in general his biggest threat was boredom compared to Schrenk who experienced brutal life threatening conditions similar to concentration camp victims.

That these men should be African American and German American respectively is even more ironic. Alexander’s treatment, as a returning POW/war hero, upon landing in New York in 1945 is undoubtedly the cruelest twist for an incredible man who so selflessly served his country.

Alexander Jefferson passed away on June 22, 2022, at the age of 100, leaving behind a legacy not only of military valor but of unwavering commitment to justice and truth. In honoring his life, we remember not only a war hero, but a trailblazer who helped shape a better, more inclusive world.

Be the first to comment