Winston Churchill wrote the first two volumes of his six volume history of The Second World War between 1946 and 1949. In chapter 30 of the second volume, he famously wrote ‘the only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril’.

With the benefit of several years hindsight, some historians believe he may have purposely exaggerated the danger. The thousands who perished defending precious vulnerable supply lines from marauding German U-boats on the high seas might beg to differ. The British Merchant Navy losses alone through 1940 and 1941 were staggering; some 779 ships sunk with 16,654 merchant seamen killed or missing. These statistics bear witness to endless stories of extraordinary sacrifice exhibited by US and Canadian merchant mariners and those of the Merchant Navy of United Kingdom.

Contribution and representation

As so often happens with The Log Book Project, our journey to Mr. David Craig began with a completely different intended profile. In terms of scale, Russia’s influence on and by WWII is perhaps the greatest of any country. The Project’s lofty goal of representing all participating nationalities of WWII would be enormously incomplete without at least one Russian signature. It was during this search that Nick Devaux discovered the Russian Arctic Convoy Museum website. The enormous contribution made by those who served in this campaign was immediately obvious. Co-opted Committee member, Bruce Hudson cautiously considered the strange request occupying his inbox from Devaux for assistance to approach their veterans.

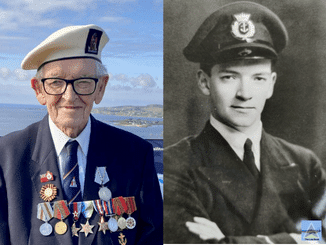

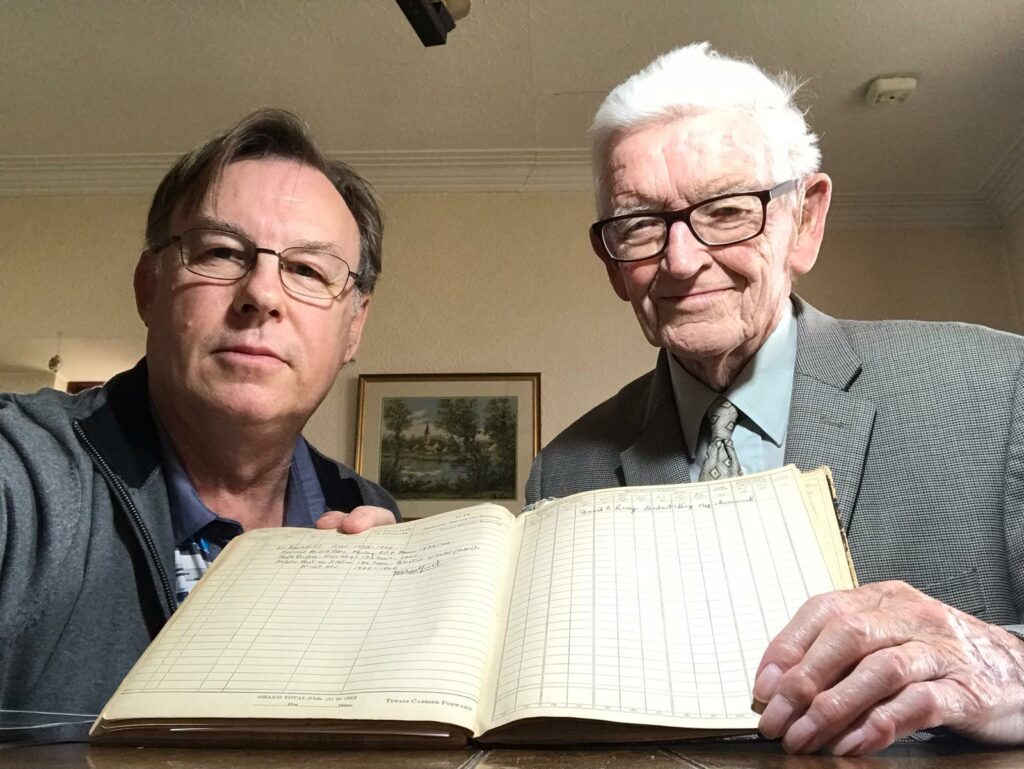

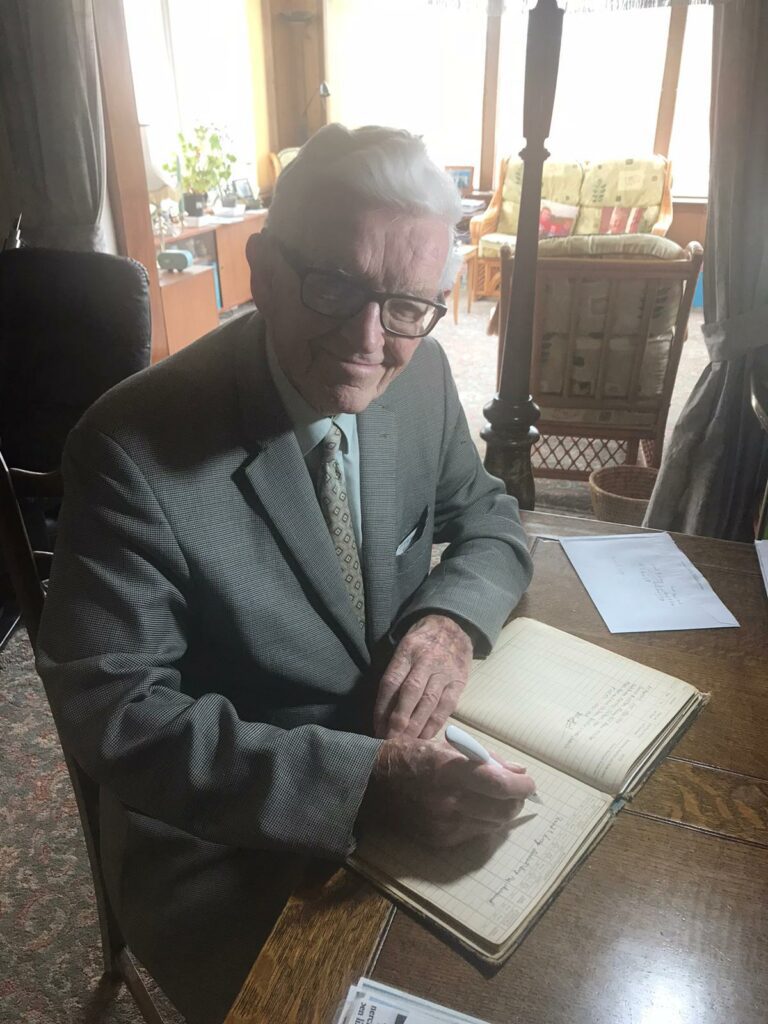

Evidently convinced of the Project’s integrity, Hudson graciously facilitated contact with David Craig and Vic Bashford; 2 remarkable veterans of this astounding campaign. UK based Project associate member Ross Stewart, himself a peacetime merchant marine veteran, was hosted by Craig in his Kilmarnock Scottish home on 15 September 2018. Ever the warm affable gentleman, Craig happily shared his experiences with Stewart and honored the Project by signing The Log Book.

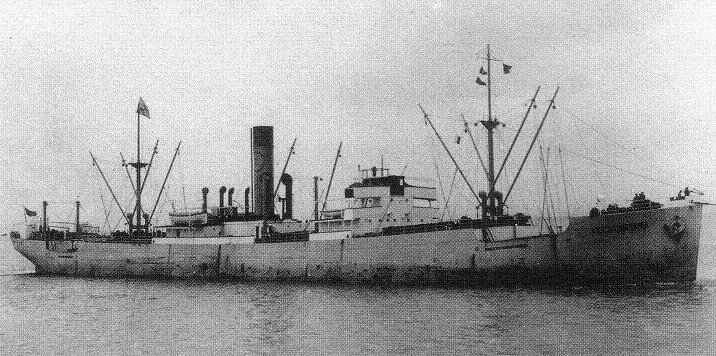

Craig joined the merchant ship SS Dover Hill as third radio officer on January 13th, 1943. The 17 year old was no green-hand having joined his first ship in 1940, aged 15. Once aboard he learned the ship was bound for North Russia.

Convoy JW 53

On February 15th 1943 the SS Dover Hill sailed in a convoy of twenty eight Merchant ships (Convoy JW 53) bound for Murmansk, Russia. The convoy soon encountered vicious seas with heavy winds and six merchant ships were damaged and diverted to Iceland along with the cruiser HMS Sheffield (C24) and escort carrier HMS Dasher (D37).

Royal Navy official photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The storm scattered the ships and by February 20th the Royal Navy escorts reformed the remaining 22 merchant ships into the convoy. The loss of their escort carrier meant no air cover and as expected, a Luftwaffe patrol aircraft spotted the convoy on February 24th. Attacks ensued by Ju 88 bombers the next day. Despite damage, the Dover Hill reached Kola inlet on the northern coast of Russia on February 27th.

Explosive visitor onboard

Anchorage in the Kola inlet provided respite from storm waves only. The Luftwaffe continued their raids relentlessly. Craig recalled one particular attack on April 4th. Two Ju 88 bombers attacked the SS Dover Hill with five 1,100 lb bombs exploding in the sea around her. A sixth went directly through her main and tween decks but miraculously failed to explode.

Craig recalls seeing the Ju 88 bombers approaching from astern with Bofors AA bursts below them. When the bombers turned away he assumed they had beaten them off and stepped out on deck. Unknown to Craig the planes had released their bombs before turning away. Five of the bombs exploded on both sides of the ship and blew Craig off his feet. As he got up a gunlayer came down from one of the bridge Oerlikons. He pointed out a round hole in the deck a few feet behind from where Craig had been standing.

I looked behind me and there was a nice hole through the steel deck where another 1000-pound bomb had gone right through. It had gone right through the deck below it and into the coal bunkers

Signaling Murmansk asking for bomb disposal personnel they learned none were available. The captain offered the crew three choices, Craig volunteered for the option to rid the ship of the bomb.

We started digging back the coal, trying to find the bomb. We didn’t know we’d have 22 feet to dig before we got to it.

David Craig on digging the bomb out of the bunker.

Unfortunately the Germans discovered what we were up to and bombed us again hoping to set off the bomb we were digging for.

Due to the bomb explosions and the concussion of our own guns, the coal fell back into the space where we were digging and things got difficult at times.

Disposal and reward

After two long days and nights the team finally managed to get the bomb up on deck. The squad precariously inscribed their names on the casing before the disposal began. Craig was one of three volunteers to support a Russian officer who came aboard to remove the detonator. As the officer began to unscrew the detonator, all cautious relief abruptly dissipated when it became stuck. Craig and his crewmates watched in horror as the Russian proceeded to hammer the side of the detonator. Eventually budging and successfully removed the bomb was dumped over the side into the Kola inlet where it probably lies to this day.

Craig, with 14 other sailors, received the King’s Commendation for Brave Conduct.

Return to UK

Craig returned with the SS Dover Hill to London on 14th December, 1943. He recalls sailing up London River towards Surrey Commercial Docks, flying the Red Ensign.

We were proud of the old ship as if she had been a spick and span Navy vessel arriving in port.

Incidentally the Red Ensign had a hole in it where an Oerlikon shell had gone through it during the fighting. But it was the only one they had left on the ship.

The fate of SS Dover Hill

Upon returning from Russia late 1943 the SS Dover Hill was repaired and taken over by the MoWT. She crossed the English channel and was scuttled as as a Corn Cob block ship in the Sword landing area, June 9th 1944. Her last known record ends as a breakwater block ship within Goosberry 5 outside Ouistreham (Sword beach).

The Russian officer

In 1987 Craig learned the name of the Russian Bomb Disposal officer: Air Force Major Pavel Alexeevich Panin of 255 IAP-SF. Through friends at the Northern Museum in Murmansk, Craig also learned that Maj Panin was killed in battle August, 1943.

Maj Panin was an ace with 13 victories and Hero of the Soviet Union recipient. 255 IAP-SF was a North Sea Fleet unit flying a mix of P-39N Airacobra’s, LaGG-3’s and Yak-1’s.

Maj Panin is reported shot down and KIA in an engagement over Bering Sea on August 26th, 1943.

Continued service and visits to Murmansk

Craig continued his service, sailing all over the world for the war’s duration. He returned to Murmansk in 1980 and with assistance from Russian authorities, paid his respects at the grave of a friend killed during the war.

Source: David Craig personal photo collection – with permission.

Craig entertained Stewart in his Kilmarnock home where the signing took place over a 3 hour visit. The two shared an instant bond as Stewart’s Merchant Navy service included several visits to Murmansk.

Arctic convoys

Wikipedia notes 78 convoys between August 1941 and May 1945 involving some 1,400 merchant ships escorted by ships of the Royal, Canadian and US navies. Facing extreme weather and constant U-boat and aircraft attack, the convoys demonstrated the Allies’ commitment to assisting the Soviet Union.

Veterans like Craig are greatly revered by the people of Murmansk and Arkhangelsk who remember the legendary sacrifices made to deliver desperately needed supplies during the darkest days of WWII. The campaign played a critical role, prior to the opening of a second front, in diverting a substantial part of Germany’s naval and air forces away from the Eastern fronts.

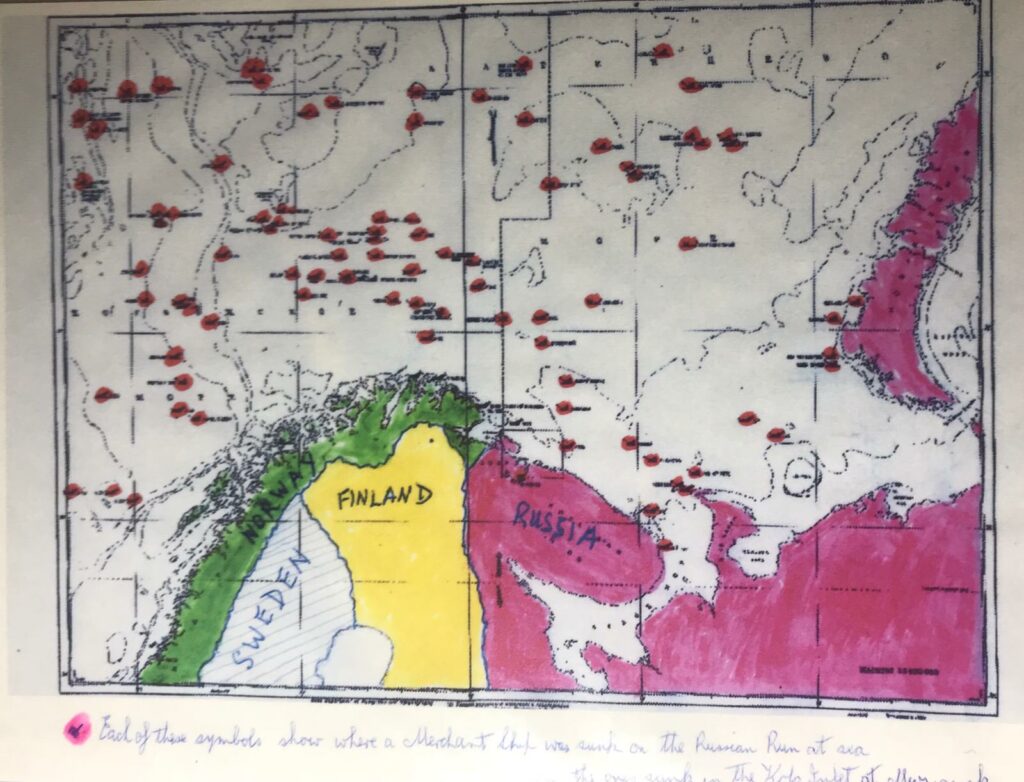

“Each of these symbols show where a Merchant ship was sunk on the Russian Run at sea.”

David Craig’s modest manner and sparkling wit belies the staggering selfless service he and so many of his colleagues demonstrated to the resounding success of the Russian Artic Convoys. His signature adds awesome stature to the Project and we are honored to relay his story. Visit the Russian Arctic Convoy Museum for more information and profiles like his.

Footnote

As it turned out, the detour to Messrs. Craig and Bashford eventually led directly to the addition of, not one but two, Russian veteran signatures. The wonderful unscripted journey continues….

Source: David Craig personal photo collection – with permission.

Be the first to comment