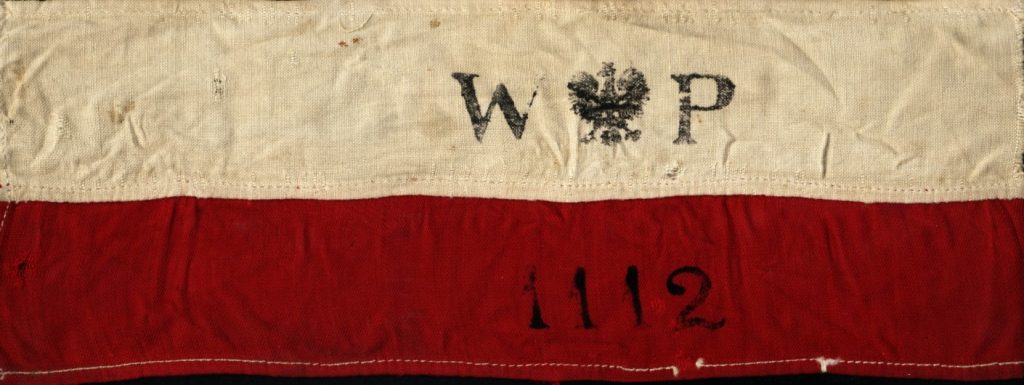

Stanislaw “Stanley” Woźniak was born 9 January, 1928 in Poland and at the tender age of 14 joined the Polish resistance. He spent part of his childhood in Rydzyna, Poznań, where his father worked at the Sułkowski Castle. These were, as he later recalled, the happiest years of his early life. However, in late August 1939, sensing the impending German invasion, his family fled back to Warsaw just days before the outbreak of World War II.

Early Life and entry into the Underground Resistance

Following the occupation, Woźniak’s childhood was marked by displacement and hardship. After a period of instability, he entered a boarding school in Otwock in 1941, where he completed primary school and began secondary education in secret, illegal classes—a dangerous but common practice in Nazi-occupied Poland. Education was pursued under the constant threat of German discovery, which could mean imprisonment or death for students and teachers alike.

While still a teenager, Woźniak was drawn into underground resistance activities. In Otwock, one of his tutors introduced him to a clandestine scout group. This seemingly innocuous activity served as his first exposure to the Polish underground. By 1942, he formally joined the Kedyw (Directorate of Sabotage and Diversion) of the Home Army (Armia Krajowa), thanks to an introduction by a fellow scout, Leon Henryk (“Wąsik”).

“Mały”, “Stasio”, “Staś”

During World War II, Polish resistance fighters relied on pseudonyms to conceal their identities and protect their families and fellow underground members. These aliases were essential for operational security, as even within a unit, fighters often knew each other only by their codenames. Pseudonyms were typically based on common names, traits, or diminutives, and fighters sometimes used multiple depending on their role or mission, often backed by falsified documents.

Stanisław Woźniak used three such pseudonyms: “Mały” (meaning “Small”), likely referencing his youth or stature; “Stasio,” a familiar diminutive of his given name; and “Staś,” an affectionate nickname. These names helped him move between roles—from courier to frontline soldier—while shielding his true identity throughout his resistance work.[1]Warsaw Uprising Museum – Stanisław Woźniak Biogram and Oral History www.1944.pl/powstancze-biogramy/stanislaw-wozniak,50006.html

At just 14 years old, Woźniak took an oath of allegiance before Dariusz Gozdawa-Gołębiowski (“Krak”) and began his work as a liaison, courier, and later a fighter. His early missions included the execution of a death sentence on a traitor and a daring rescue of a wounded resistance officer from a Warsaw hospital infiltrated by German forces.

In 1943, Woźniak took part in a failed partisan expedition beyond the Bug River. The mission ended in a deadly ambush by German forces, leading to the death of the expedition commander and the dispersion of the unit. Following this setback, he lost contact with his commander and was unaware of the precise plans for the anticipated uprising.

The Warsaw Uprising: Combat and Commitment at Sixteen

Despite losing contact with his unit, Woźniak sensed the rising tension in Warsaw in late July 1944. He contacted the family of a fallen comrade and was directed to the Kamler furniture factory, where he arrived on the afternoon of August 1, 1944. The Warsaw Uprising was scheduled to begin at 5:00 p.m., but due to a premature skirmish, fighting broke out early at his location—meaning Woźniak found himself in combat within moments of reporting for duty.

The 7th Lublin Uhlan Regiment, originally a cavalry unit of the Polish Army, was reconstituted during World War II as a part of the underground resistance within the Home Army (Armia Krajowa). After Poland’s defeat in 1939, many of its prewar military units, including the 7th Uhlans, were reorganized clandestinely. The regiment adopted a partisan structure and operated under the name “7th Lublin Uhlan Regiment ‘Jeleń'” within the Warsaw District. It functioned as a combat and liaison unit, engaging in sabotage, armed resistance, and intelligence activities. During the Warsaw Uprising of 1944, its elements—including platoon 1112—played active roles in battles across Wola, the Old Town, and Śródmieście, contributing to key missions such as defending command centers and escorting the underground government.

Woźniak joined Platoon 1112 of the 7th Lublin Uhlan Regiment “Jeleń”, part of the Home Army’s Warsaw forces. The platoon was assigned to protect the headquarters of the Home Army Command and the Polish Government Delegation, both based in the Kamler factory. Within hours, he was defending key strategic sites, including the Tobacco Monopoly factory nearby.

With German pressure mounting in the Wola district, the Home Army command decided to move to the Old Town. Woźniak and another soldier were tasked with a high-risk reconnaissance mission to find a safe route through the ruins of the former Jewish Ghetto. Though their first sewer mission went awry, reaching the Vistula instead of Śródmieście, they marked the path and returned safely. The next team used their intelligence to successfully transfer the command structure to the Old Town.

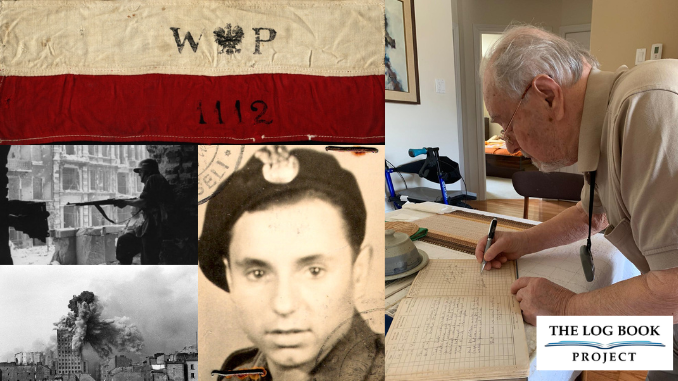

Below photograph shows Wozniak’s armband. This type of armband was worn by members of the Armia Krajowa (Home Army) or other resistance fighters during the Warsaw Uprising against Nazi German occupation. The use of such identifiers was crucial during the uprising, as it provided a visible sign of combatant status in the absence of formal uniforms.

Frontline Battles and the Old Town Inferno

In the Old Town, Woźniak’s platoon shifted between guarding the General Staff and manning volatile frontlines. He helped defend St. John’s Cathedral in alternating shifts with the “Wigry” platoon, enduring relentless German and Ukrainian attacks. He described spending two weeks in the narrow corridor between the cathedral and the Royal Castle under constant fire.

The fighting intensified as German forces encroached on the Old Town. Woźniak participated in key battles at Jan Boży Hospital, the Church of the Revelation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and Krasiński Palace. When a German explosive-laden tank destroyed part of the district, he narrowly avoided death by being stationed elsewhere.

Nearly 85% of the Polish capital was destroyed in the fighting, the scale of the destruction is hard to imagine, the below video at least gives a small peak.[5]https://go2warsaw.pl/en/warsaw-uprising/

Sewers, Survival, and Śródmieście

On September 1, 1944, as the Old Town’s fall became inevitable, Woźniak was ordered to help evacuate the remaining forces through Warsaw’s infamous sewers. He carried wounded soldiers, including his platoon commander, through narrow, foul-smelling tunnels beneath enemy positions. He described the trauma of stepping over corpses and emerging on Warecka Street feeling as though he had reached heaven.

Once in Śródmieście, the decimated Platoon 1112 was reassigned as a security unit for General “Monter” Chruściel’s Warsaw District Headquarters, based in the Palladium Cinema on Złota Street. Woźniak took up guard and observation duties, continuing to defend Warsaw until the Uprising’s surrender in early October.

The below image comes from Wozniak’s personal collection, translating the label adding context to the information a most profound story emerges.

“Command Headquarters Protection Platoon, Uprising, Palladium Cinema, Złota Street = 15 September 1944”

The well-known cinema, Kino Palladium, on Złota Street in central Warsaw was, as many buildings during the uprising, repurposed by the resistance for military use — as command posts, hospitals, or barracks.

“Pluton Ochrony Dowództwa Powstania” was a special protection unit responsible for guarding the command staff of the uprising.

The date 15 September 1944 falls in the later stages of the uprising, when fighting was especially intense and the situation for the Polish insurgents had become critical due to lack of supplies and reinforcements.

The identities of the persons in the picture are unknown.

For his bravery during the uprising Wozniak was awarded the Cross of Valour and promoted to senior uhlan.

Captivity and Liberation

Following the Uprising’s capitulation, Woźniak, now just 17, chose to go into German captivity rather than remain under Soviet influence. He was deported to Stalag XI B in Fallingbostel and later to Stalag VI J in Dorsten, working in a forced labor detail in Mönchengladbach. After escaping briefly, he was recaptured and returned to the camp, which was ultimately liberated by the British Army on April 15, 1945.

Post-War Life in Exile

After the war, Woźniak joined the Polish II Corps in Italy, where he resumed his education at the 5th Kresowa Division Gymnasium in Modena. He later continued his studies in England and completed his education at the University of Toronto after emigrating to Canada in 1951.

Woźniak built a successful civilian life in Canada, working his way up from accountant to director and treasurer of a Ford-affiliated company. He became a prominent member of the Polish diaspora, serving as vice-president of the Home Army Circle in Toronto and participating in local and federal politics.

In 1964, he married a German woman he had met in 1960. This decision was not easy for him—he struggled for four years with the idea of marrying someone from a country whose regime had inflicted so much suffering during the war. Ultimately, he decided not to hold her responsible for the actions of her nation:

“She was born in Germany, just as I was born in Poland… but I struggled for four years with whether to marry her or not… Finally, I came to the conclusion – what did she have to do with it?”

Legacy and Reflection

Stanisław Woźniak remained a passionate defender of the Uprising’s necessity. In a 2007 oral history interview, he emphasized the moral and historical importance of the struggle, stating:

“Of course [it made sense]! And who knows what would have happened if the Uprising had not happened?”

Woźniak’s story stands as a testament to the courage, resilience, and dedication of Warsaw’s youth—who, despite their age, fought with honor in one of the most desperate and heroic chapters of Polish history.

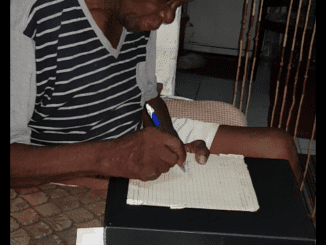

Obtaining the signature

We are indebted to Jaxon Hekkenberg, a young teenager from Shanty Bay in Ontario, Canada who founded his own project interviewing veterans of WWII. We have frequent contact and when he made us aware of Wozniak and offered to facilitate a signing event we were quick to accept.

On 25 April, 2022 the project was honored by Wozniak’s signature. His entry adds immense gravitas to the project and allows us to illuminate and pay tribute to the sacrifices made during the Warsaw Uprising.

Sources and further reading

The primary sources for this profile is

The translated version of Wozniak’s profile as published on the Warsaw Uprising Museum website: https://www.1944.pl/powstancze-biogramy/stanislaw-wozniak,50006.html

The profile and interview published by the Crestwood Oral History Project: https://www.crestwood.on.ca/ohp/wozniak-stanley/

Information found on Go To Warsaw website: https://go2warsaw.pl/en/warsaw-uprising/

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/warsaw-rising-the-battle-for-polands-capital/

References

Be the first to comment