Wilbur Showell Bryans was born April 3, 1922 in Sullivan Township, Ontario. Assigned to the Royal Canadian Medical Corps and stationed in Basingstoke, UK, he witnessed many horrific injuries sustained through combat.

Growing up on a farm Bryans then attended the local two-room school house before moving on to business school in Owen Sound. Here Bryans picked up critical skills that would impact his time in the military.

Called up in 1941 Bryans reported to the Horse Palace in Toronto and then did basic training in Camp Borden. Not long after he was on his way to Halifax, where he boarded the SS Île de France for the trans-Atlantic journey.

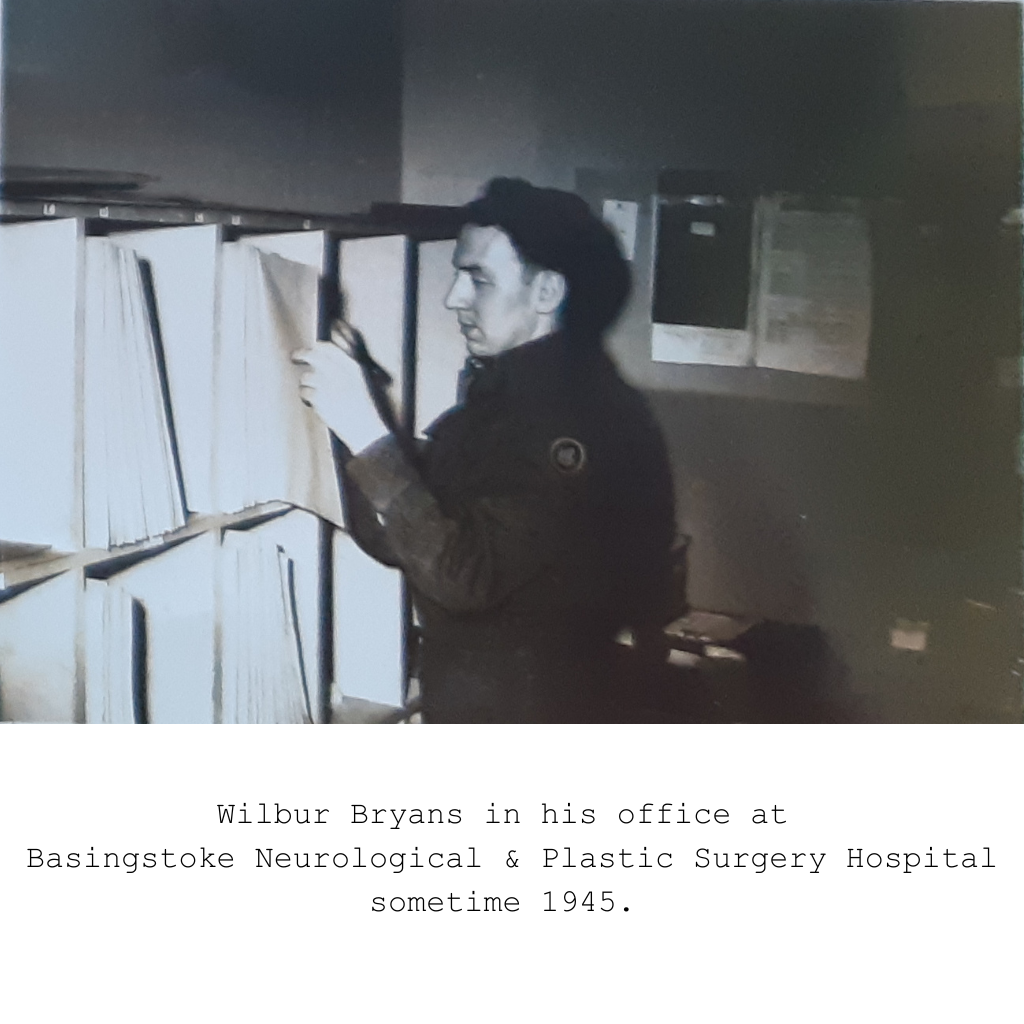

On arrival to England Bryans was transferred to Aldershot, where the typical military training continued. After some time the military identified some of Bryans’s skills he had learned at business school before enlisting, notably shorthand and typing.

Shorthand is an abbreviated symbolic writing method that increases speed and brevity of writing. The process of writing in shorthand is called stenography and was more widely used before the invention of recording and dictation machines.

Bryans’s ability to write in shorthand was noted and he was transferred to the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps (RCAMC).

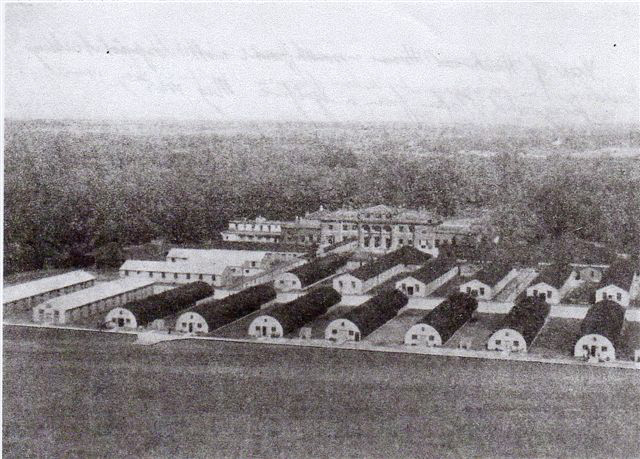

BN&PS Hospital at Hackwood Park

In 1940 the large country estate, including Hackwood House, was gifted to the Royal Canadian Army as a hospital, free of payment, but on the condition it was returned after the war.[1]https://www.friendsofthewillis.org.uk/articles/the-story-of-hackwood-park/ Located just south of Basingstoke in Hampshire the estate was turned into a psychiatric hospital

By 1945 it had become Basingstoke Neurological and Plastic Surgery Hospital treating the terrific injuries of war and here Bryans was assigned to the X-ray department working for Dr. Eaglesham who Bryans speaks highly of.

Major Douglas Cameron Eaglesham

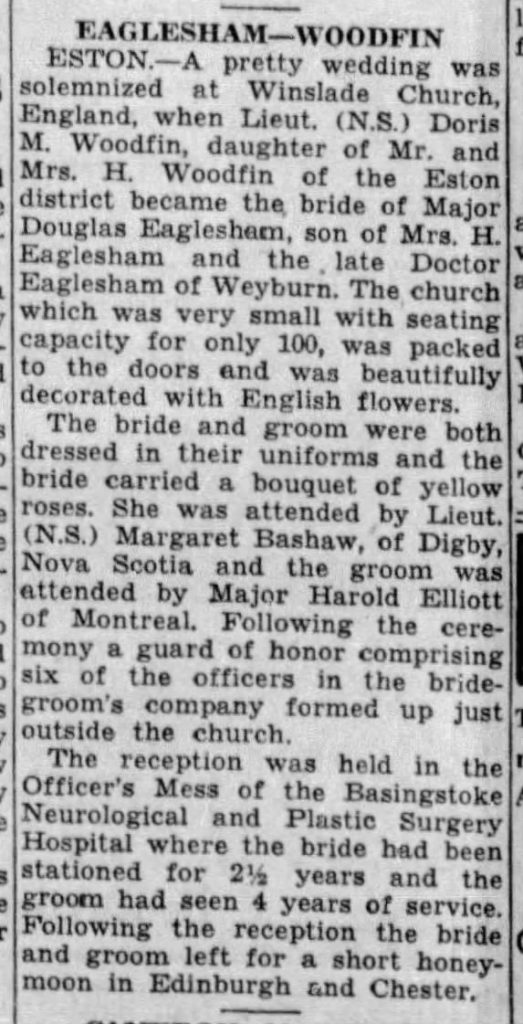

It is in Basingstoke that Dr. Douglas Cameron Eaglesham met and married RCAMC nurse Doris Mabel Woodfin. They were married at Church of St Mary at Winslade in June of 1945 with a guard of honor forming up just outside the church to welcome the newly wed couple.

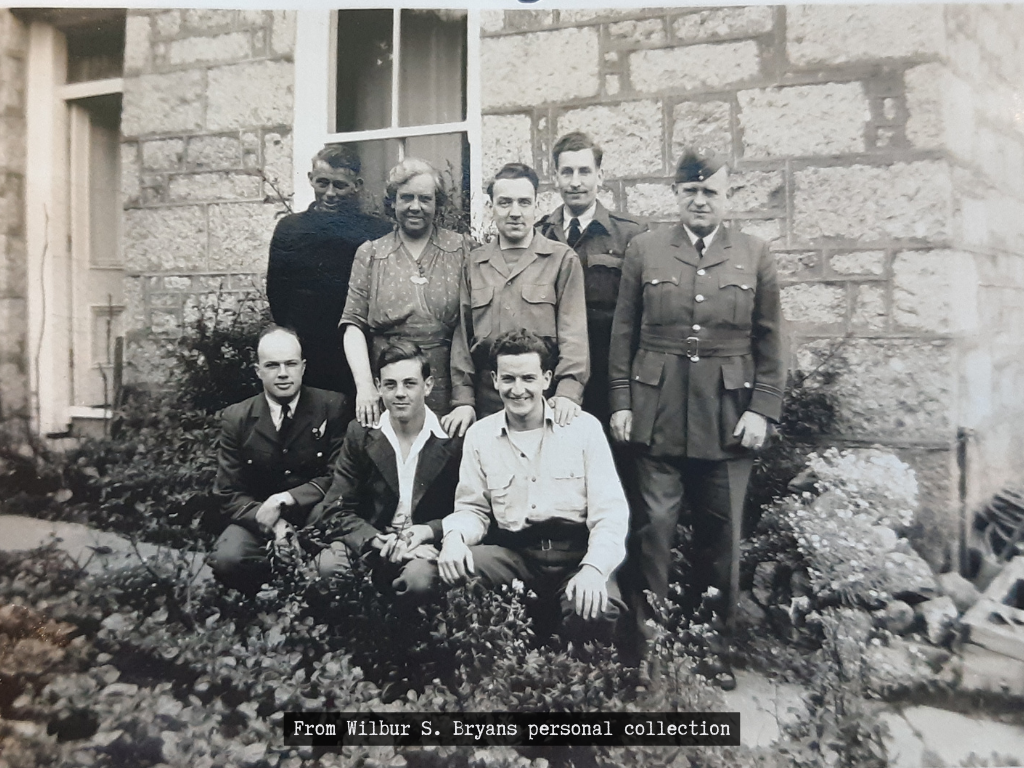

Bryans was in attendance as the occasion is captured in below photographs kept within his personal collection. Following the ceremony a reception was held in the Officer’s Mess of the Basingstoke Hospital.[5]Star-Phoenix, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada, Tuesday 7th of August 1945

The church is today no longer in use but listed as a Grade II building marking it as a building of significant historic importance.

Dr Eaglesham would continue after the war and became involved in introducing Neuroradiology to Toronto General Hospital until leaving to start practice in Guelph, Ontario.

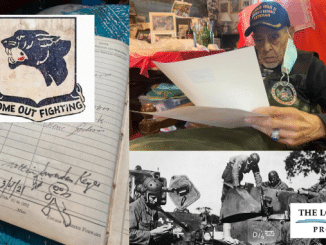

Wilbur Bryans collection via Crestwood OHP

Victims of war

Many of the patients treated were airmen who often suffered horrendous burns sustained from inflight fires as a result of aerial combat. He recalls turning white, and having to go down the hallway, the first time he saw a burn casualty as he could not see it. “Skeletons walking around” he explains to Scott Masters in a June 2022 Crestwood OHP interview.

With his proficiency writing in shorthand he was tasked with taking notes as the doctor treated patients. Bryans was always fearful in doing so as he did not know the strokes for the medical terms used, so his solution was to leave space for the doctor to write it in later.

In both World War I and World War II approximately seven percent of battle casualties were due to cranial injuries.[8]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7576391/ Bryans recalls one encounter in Ward 6 with a young fellow from Norway, a fighter pilot that had been shot down during a dogfight, now paralyzed from the neck down. The pilot had received his training in “Little Norway” which was a Royal Norwegian Air Force training camp setup in Ontario, Canada. The pilot did not make it as far as Bryans can recollect.

No. 4 Canadian General Hospital

When the No. 8 Canadian General Hospital (CGH) was deployed to Normandy in support of the D-day landings No. 4 CGH replaced them at Connaught Military Hospital in Aldershot, just a short distance from Farnborough.[9]https://www.friendsofthealdershotmilitarymuseum.org.uk/garrison.21A.html

Serving a little over a year at Basingstoke Hospital, Bryans moved to No. 4 Canadian General Hospital (CGH).

The hospital played a vital role in the massive organization developed to treat casualties from the Normandy landings. From June 1944 to the end of May 1945 nearly 399 000 patients in total were evacuated by air on cross-channel flights to various places in the UK.

79363AC – Nurse Katye Swope, a member of the 802d Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron, checks the litter patients aboard a plane for evacuation from Agriegento, Sicily, to Africa for further medical treatment. (25 July 1943)

Credit Photo to the National Museum of the USAF[10]https://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/Visit/Museum-Exhibits/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/196161/winged-angels-usaaf-flight-nurses-in-wwii/

The first D-Day casualties arrived at the Connaught received by No. 4 CGH on 8 June 1944, of the 278 men received only three were Canadians. Bryans clearly recall the steady stream of evacuees coming in from early morning around 6 am to the evening.

Denham Meek, a technician at the Connaught, provides a profound description of the process in an article by Paul H. Vickers at Friends of the Aldershot Military Museum.

The casualty was grabbed in France, bleeding stopped, given the simplest first-aid treatment and evacuated to an airfield where they were put into quarters with the Red Cross, and there was a steady circuit of Dakotas from France to Farnborough airport. From Farnborough we had a circle of ambulances, they used a different route coming and going, and those casualties reached us. A casualty could reach us within two hours of being wounded, the mud on him was still wet often, and so the degree of medical attention was extremely rapid.

Something receiving less illumination in history books are the many casualties with battle fatigue and other psychiatric disorders. Bryans remembers tending to a soldier he had met on the ship coming across the Atlantic. Having come ashore through the carnage during the D-day landings he told Bryans “I just stood there screaming, I just went crazy.” The soldier was brought back to the UK and would need medication to calm him down.

It is through stories like Bryans’s wartime service that one starts to sense the massive scale of the organization that existed behind the front lines. To be able to bring an injured soldier back to the UK for treatment from a battlefield in Normandy within hours, in 1944, is as impressive as it is staggering.

After the war and returning home

With Bryans clerking skills he helped set up an office that brought entertainment for the troops. After the war he also assisted in organizing the massive amounts of paperwork raised in the repatriation depots.

Bryans came back to Canada in February 1946, beginning the difficult process of readjusting to civilian life. Back home he joined his father in a honey business and later obtained work with the federal Government.[12]https://www.rushnellfuneralhomes.com/memorials/wilbur-bryans/5262323/ Work and family helped to get him through, and soon the rhythms of postwar life fell in place.

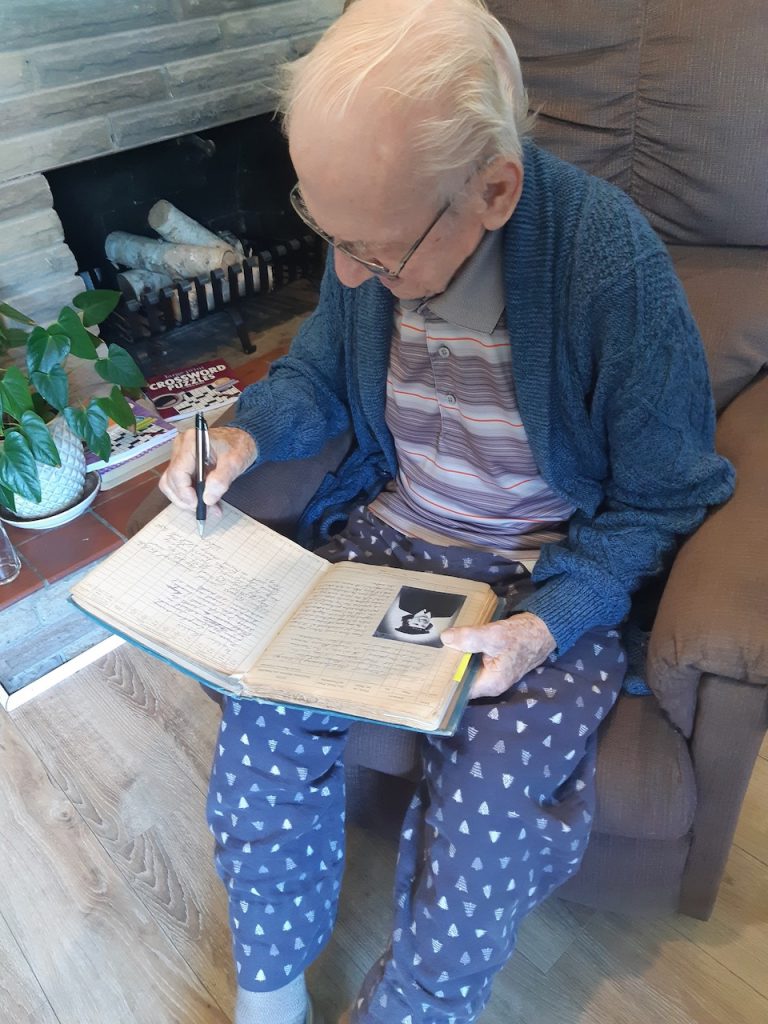

Mr Wilbur Showell Bryans signed the log book on 3 June 2023 under the facilitation of Scott Masters. His entry bestows gravitas to our project and joins Mrs Madeline Shavalier in representing the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps (RCAMC).

Sadly we learned of Mr Bryan’s passing on 20 August 2023, we are very honored to have been given this peak into his service and will do our utmost to help carry his legacy for posterity. May he rest in perfect peace – we have the watch.

This profile is in large parts copied and developed from its original as published on the website of Crestwood Preparatory College, we are forever indebted to Mr Scott Masters and his students.

Taken in front of St. CLements Villa, The Parade, Mousehole, Penzance, Cornwall, May 45″

cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Mr Ignavy – geograph.org.uk/p/818002

References

Be the first to comment